This devlog is about the journey. If you just want to try the game: Play Online.

Back in early December last year, my wife and I took a trip to Japan. At the Tsutaya Books in Daikanyama, Tokyo, I spotted this board game for sale:

The game is called “Nego”—plaster cat-shaped pieces played with the original rules of Go. The name is a portmanteau of “Neco” (Japanese for cat) + “Go” (the board game).

I didn’t end up buying it, but I quite liked this kind of small game that takes familiar rules and gives them a simple twist for a brief moment of novelty. Board games are the perfect medium for this. As I continued browsing the bookstore, half my brain quietly switched into game designer mode.

Among board games, the only one I can say I’m “decent” at is Chinese Chess (Xiangqi). My late grandfather started teaching me when I was very young—“the knight moves in an L-shape, the elephant moves diagonally two squares.” Back then, among all my relatives, he was the only one whom I can’t win. Before I left my hometown, his handicap against me had gradually shrunk to just one knight (if I had synesthesia, “knight” would taste like “seasoned wisdom”). I kept taking chess classes throughout elementary school and would buy puzzle books full of endgame problems to work through on my own. Though I basically stopped playing after fifth grade (that’s another story), chess has always held a special place in my heart.

Inspired by Nego’s geometric shape variations, my initial idea was to combine two chess pieces into one “compound piece” that occupies two squares, unlocking new abilities. For example, “Knight/马” + “Chariot (Rook)/车” = “Knight-Chariot/马车.” This is a wordplay that only works in Chinese (马车 means “wagon”)—but I quickly abandoned this “piece-clustering” concept. Nego’s shape variations directly interact with Go’s core mechanic of “surrounding,” but they wouldn’t enhance Chess’s distinctive feature—using pieces with different abilities in coordinated attack and defense. However, following the thread of “wordplay,” I had a more interesting association:

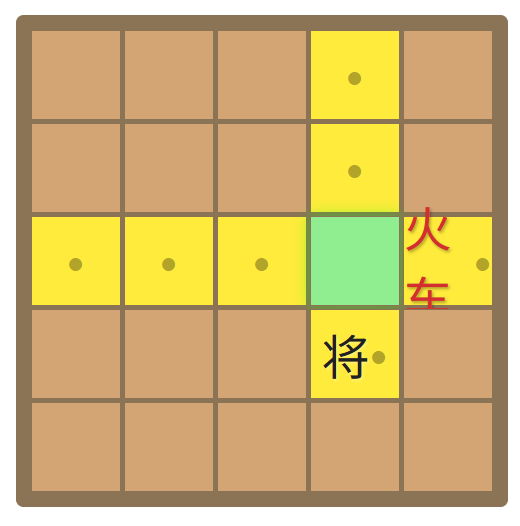

- “Fire” + “Chariot” = “Fire Chariot” (火车: “train” in Chinese)

- “Water” + “Chariot” = “Water Chariot” (水车: water wheel)

- “Wind” + “Chariot” = “Wind Chariot” (风车: windmill)

- “Lightning” + “Chariot” = “Lightning Chariot” (电车: electric tram or EV)

These four compound words, the objects they represent, the four classical elements, and the “Chariot” piece in Chinese Chess—they all connect in delightfully unexpected ways. This provided natural inspiration for the combined pieces’ abilities. In that moment, ChessElementa’s core “element” combination mechanic—based on Chinese character compounds—took shape.

For the gameplay loop, I immediately zeroed in on “endgame puzzles.” I could use the classic “continuous check” format—where Red must check Black on every move—to showcase the new piece abilities while keeping the game tight and engaging. After all, this is a format that hundreds of years of Chess/Xiangqi endgame design have refined. My working title, scribbled in my notebook at the time, was the rather uninspired “Check On.” Later, for various reasons, I didn’t use “continuous check” as the guiding constraint, relaxing it to “win within 3-5 moves”—keeping each puzzle’s playtime and complexity within casual mobile game territory.

But it was all just idle musing—I had no intention of actually building it. After all, my last game took a year and a half to finish. I was thoroughly once bitten, twice shy.

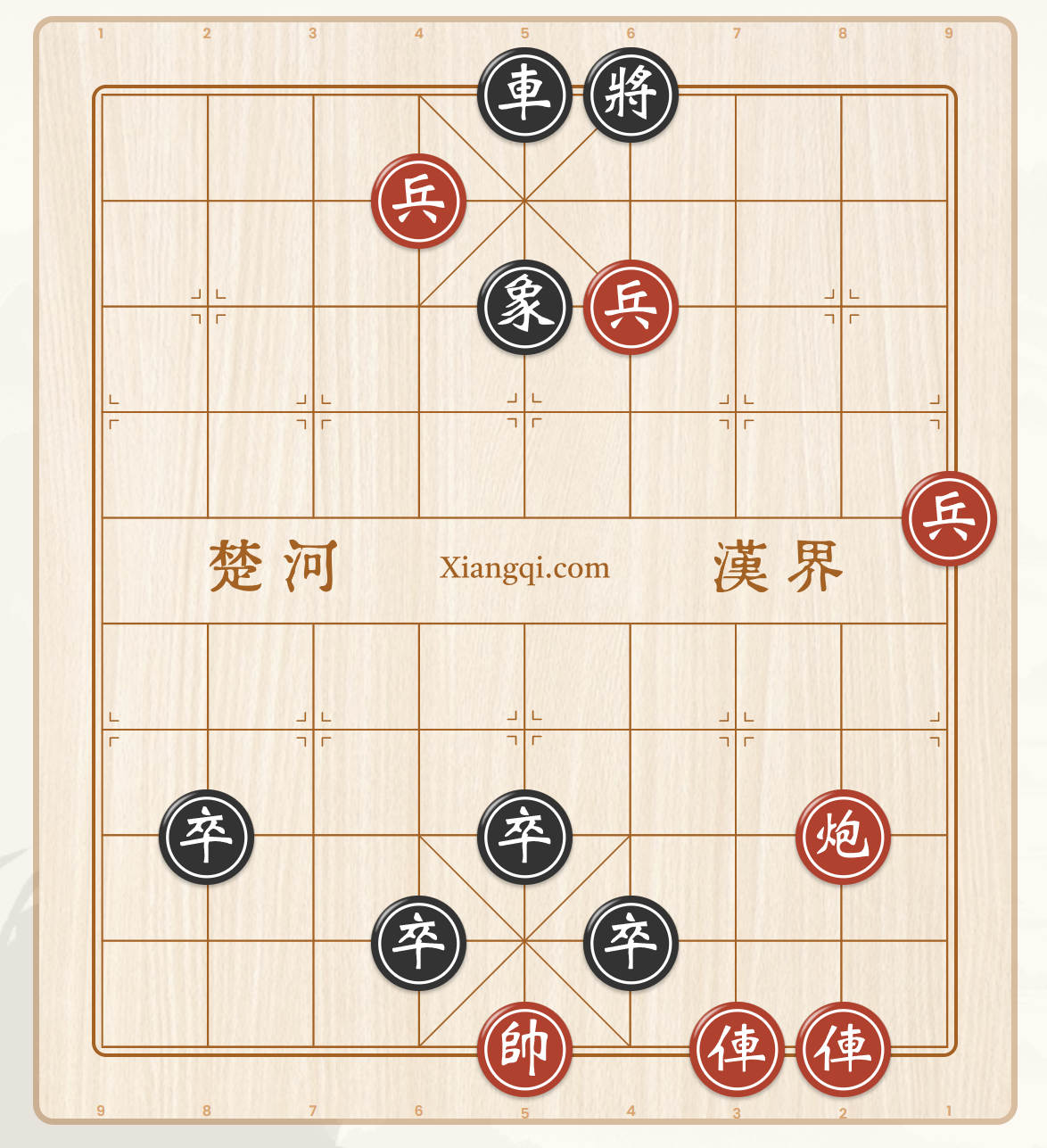

One day in late December, with nothing better to do, I downloaded Google’s AI code editor Antigravity to test current Browser Use Agent capabilities. As my test project, I described this game idea. Here’s what the first version of code produced:

Crude as it was, being able to visualize the game was invaluable. After a few quick tests, I soon realized the game wasn’t as fun as I’d imagined. I had overlooked one obvious critical factor: the Black pieces’ AI.

What makes chess endgame puzzles engaging—whether through “continuous checks” or “quiet moves” (seemingly passive moves that leave the opponent in a losing position no matter how they respond)—is built on the enemy’s “rational response.” As a kid working through endgame puzzles, I was also playing the opponent’s role, switching perspectives to think through their moves. This ensures that each move from both sides has a rational tension. With just the element fusion mechanic and a rough gameplay framework, this AI-less prototype couldn’t deliver that satisfying tension.

Integrating an AI engine isn’t conceptually difficult. Traditional chess engines have open-source versions (International Chess has Stockfish, Chinese Chess has Pikafish). Modern AlphaZero has many open-source implementations too. Worst case, I could hand-code one from scratch in PyTorch—it’s not like I don’t know how.

But it takes time. After all, my last game took a year and a half to finish. I was thoroughly once bitten, twice shy.

Besides, I didn’t actually want to replicate the full strategic complexity of chess. In my mind, this should be a small game that provides half an hour of novelty during idle moments and brings a few smiles—just like the board game Nego, nothing more. It’s not real chess. It’s a distilled, bite-sized experience capturing the puzzle-box thinking pleasure of chess endgames.

So, after spending a day hacking together a minimum viable prototype, the idea was shelved once again.

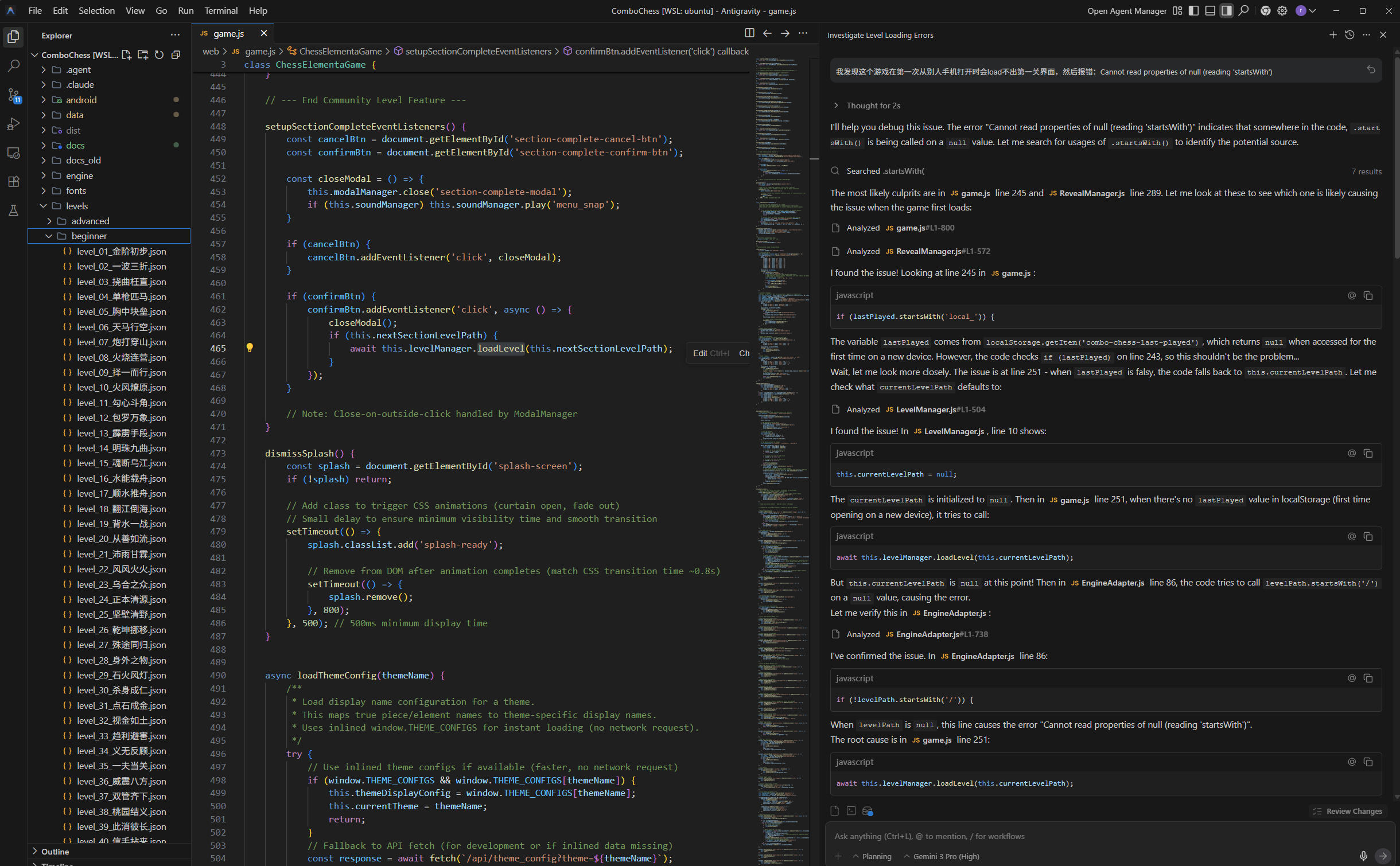

But this experience with Antigravity was quite pleasant. I’d used Claude Code before, but the quota would vanish instantly, making it impossible to focus on completing anything. Google’s quota, however, was extremely generous: for the same $20 subscription, not only was their Claude Opus quota significantly higher than Anthropic’s own, but Gemini 3 Pro was essentially unlimited. The contrast was even starker because last time—my first game—I’d done most of the work hands-on in Godot with a learning mindset. Godot is an engine designed for intuitive developer interaction, with many features that only make sense when adjusted manually in the interface. This means LLMs struggle to work with it. This time, the prototype used vanilla web frontend (JavaScript/HTML/CSS)—steel, concrete, bricks, all in code, and among the most common data in LLM training sets.

So I didn’t write a single line of code, didn’t even read any code—I don’t know JavaScript at all. This was my first time directing an LLM to complete a prototype implementation using only natural language—Chinese—without understanding the tech stack or reviewing any code. It felt magical.

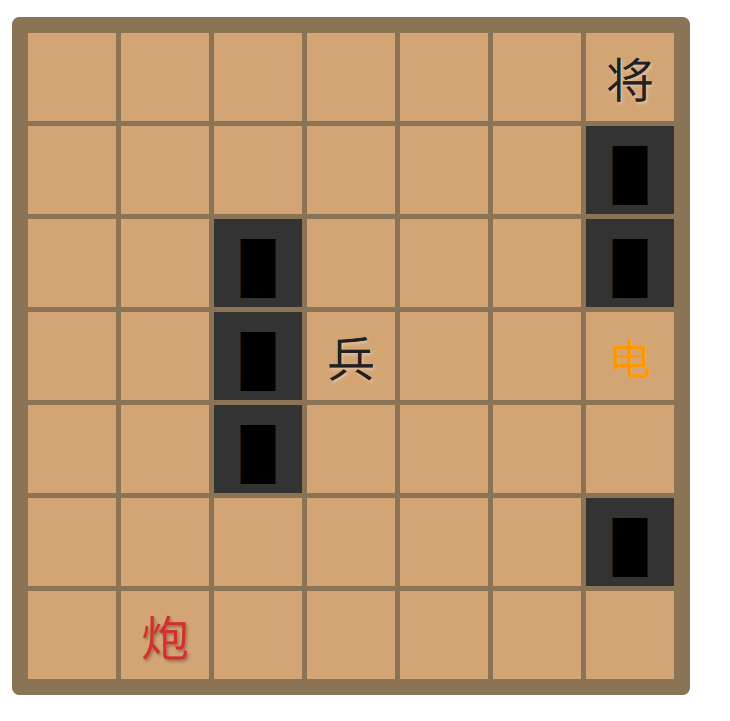

On January 11th this year, I picked up this prototype project again. One reason was a flash of inspiration for a low-cost solution to the Black AI problem: asymmetric rules. This game is fundamentally a puzzle game. The enemy AI exists purely to prevent the player from checkmating Black within the move limit while encouraging strategic thinking. This doesn’t require the AI to engage in fully rational multi-step reasoning. The AI can be dumb. In fact, a dumb AI makes it easier for players to predict its behavior and plan accordingly in a casual game. But what about the tension? My solution: give each enemy piece its own independent AI behavior. “Independent” means that in a single turn, multiple Black pieces might act according to their own rules. Meanwhile, the player still only moves once.

This defies the intuition of turn-based games. Either one side moves one piece, or—like in tactics games—both sides’ pieces can each act once per turn. But “I move once, enemies move many times” suits this game’s puzzle format: Red must win within N moves, so it’s already mechanically asymmetric—in most levels, Red doesn’t even have a King, only attacking pieces. Once I understood this, I could design simple, predictable behavior rules for enemy pieces while flexibly adjusting the number of AI pieces to fine-tune each turn’s pressure and cognitive load. And “defeating many with few,” “wit over brute force”—that fits the game’s theme perfectly.

And so, the final piece of ChessElementa was found. The mini game’s framework was now crystal clear and ready for implementation.

I got to work directing the AI. On the night of January 16th, I couldn’t help posting on social media:

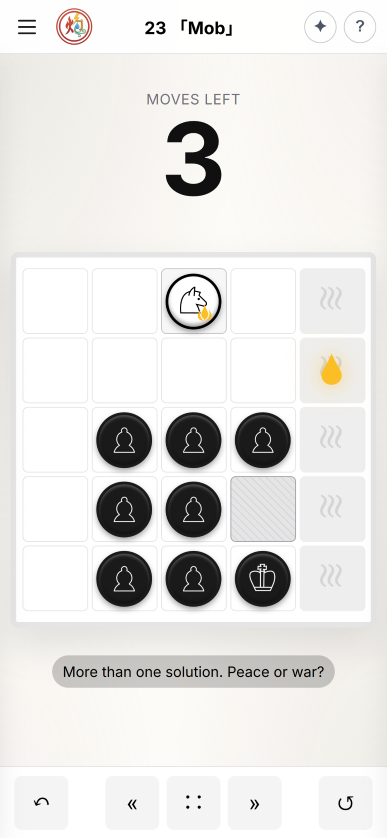

In exactly six days, I made an original-mechanic pure JS web game. Other than tweaking some CSS colors, I didn’t read or write a single line of code. Couldn’t anyway—I know nothing about JS/frontend. What you can’t see from the screenshots is that four of those days were spent polishing and fine-tuning animations, particles, sound effects, and UI responsiveness. The core mechanics were prototyped and validated in just two days. I’m very happy with how it feels now. From start to finish, Claude/Gemini wrote everything in Antigravity. My job was testing and giving directions, finding sound effects online and processing them, and using their level editor to design puzzles (AI puzzle design is absolutely atrocious). Let me put it this way: there’s really no excuse anymore for not being able to make things or learn things…

The screenshots I posted then were already quite close to the final version. Being able to polish animation fluidity and audiovisual feel to a level I thought only hands-on Godot work could achieve—all just by talking—was completely unexpected.

Development continued until January 31st. Additional features included:

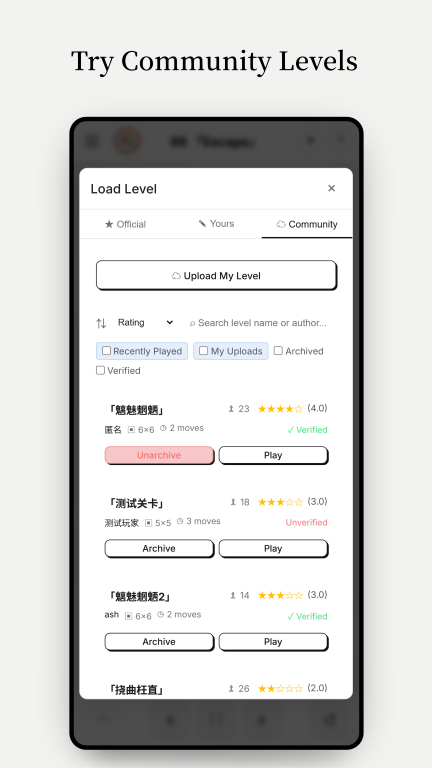

- Custom level editor

- Cloud database for community levels

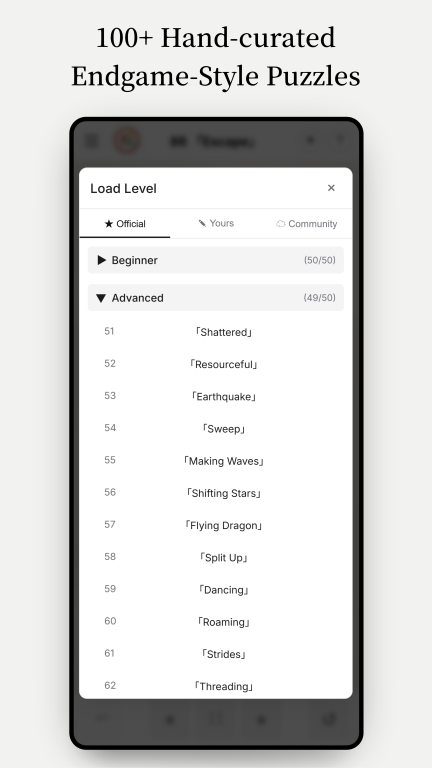

- Expanded from 40 to 100 puzzle levels

- (Unused) Pipeline testing for procedurally generated and AI-generated levels. Even with 100 example levels, still terrible.

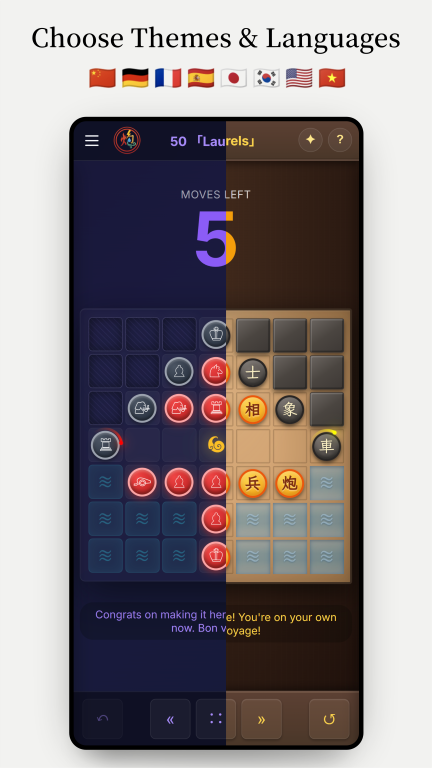

- Support for eight languages, switchable between Chinese characters and Western-style piece icons

- Multiple code refactors and cleanups

- Android app packaging and adaptation (including rewarded ads—just… wanted the experience)

- Play Store and TapTap platform launch preparation and promotional materials

I designed the puzzles, selected the sound effects, icons, and fonts from public domain assets, and hand-adjusted some CSS. Everything else was AI work that I reviewed.

The Google Play version is currently in closed testing and will launch soon. Going through the platform process was about experiencing “the whole package”, but you’ve already read this post—the link at the beginning is ChessElementa in its entirety. Free, no ads, playable offline.

20 days to make a small game I can put on app stores without embarrassment, with no prior frontend/app development experience—that’s neat. No trauma this time. Thank you, AI era.