Written in Chinese, translated by Claude Opus 4.6.

This was my first time launching a mobile game, and I learned a thing or two. Here’s a quick rundown of the considerations, the process, and the pitfalls I encountered along the way.

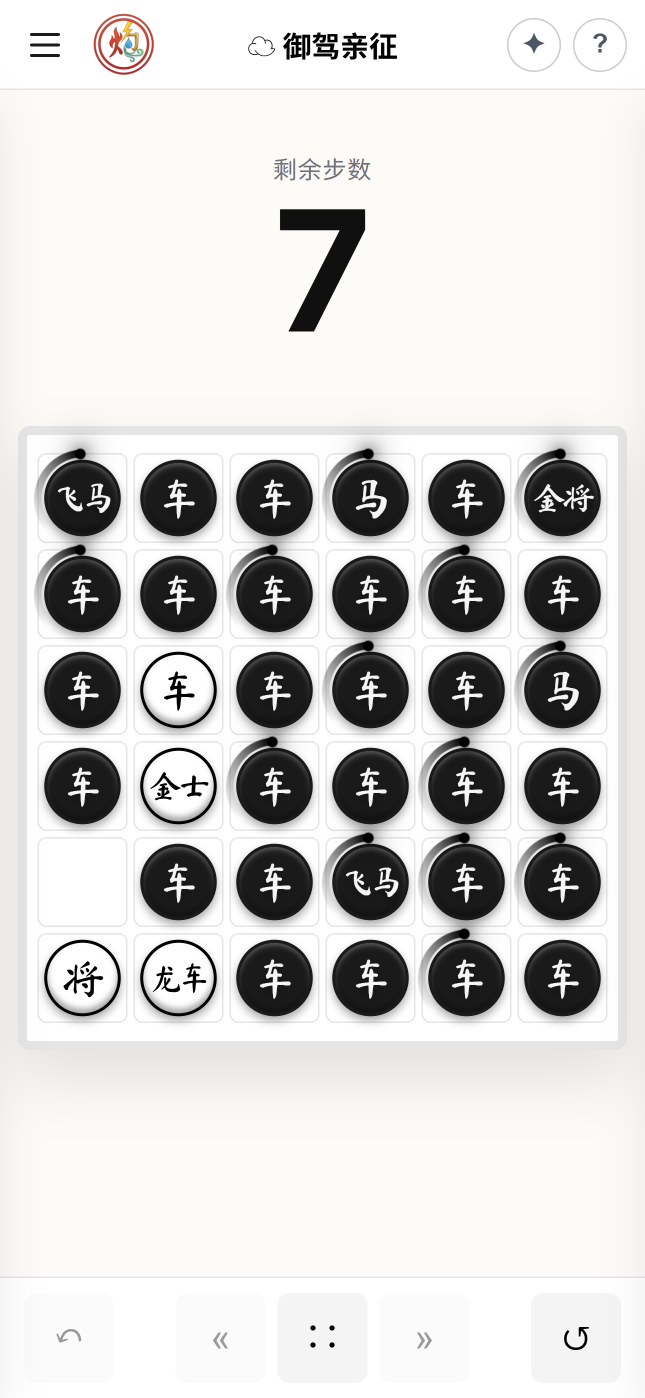

In my last devlog two weeks ago, I wrote about the journey of making ChessElementa: to loosely summarize, it was the impulsive byproduct of procrastination. It’s a tiny casual puzzle game. Originally I just wanted to spend two days building a web version to see if the core mechanic was any fun. The full production ended up taking around 20 days, not counting subsequent bug fixes and updates. A lot of what I did was purely “for the experience”—savoring the twists and turns of the road. Especially the part where I insisted on cramming ads into the Google Play version…

A week ago, the game went live on TapTap. Two days ago, it launched on Google Play. This project can now be considered wrapped up.

- Web version: Play online

- TapTap: Store page

- Google Play: Store page

- The only version with monetization ads

Key Takeaways

- Wrapping a web app into a simple Android shell is a poor fit for the domestic (Chinese) mobile ecosystem, due to fragmented browser engine versions

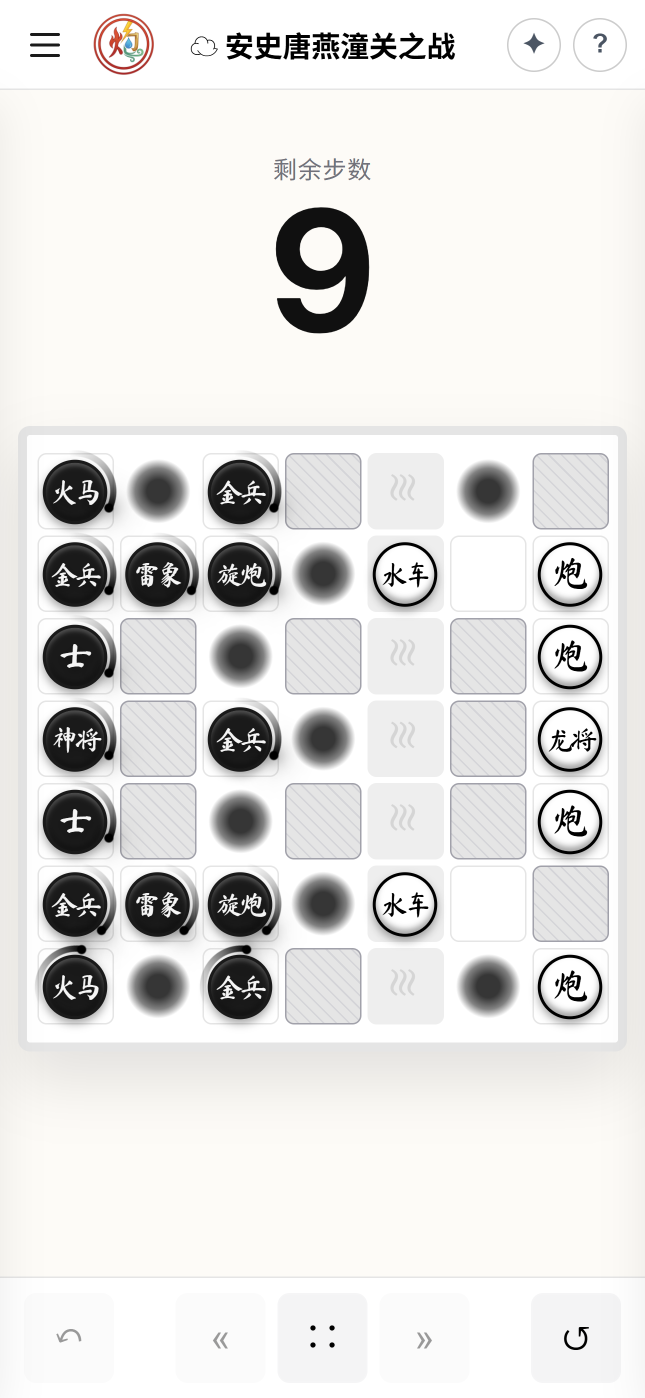

- TapTap currently has the lowest barrier in China to entry and the shortest process for publishing free single-player mobile games

- Google Play’s new policies have raised the bar for indie developers while giving new apps virtually zero organic traffic, making cold starts extremely difficult

Tech Stack

This is relevant to platform feasibility, so I’ll cover it first. If you’re familiar with frontend development or don’t care about this, feel free to skip to the “Publishing Platforms” section.

ChessElementa is a static web game built on HTML/CSS/JS with no backend server (aside from the database for community levels). Since I had AI write the code from scratch, there are no library dependencies other than some off-the-shelf open-source animation/sound effect plugins. A friend previously tried to reverse-engineer the web version with AI and guessed I used React/Vue/Tailwind/chess.js/Stockfish and the like—but none of that was used. The AI agent wrote everything “by hand”. The game UI adapts to different window sizes, including desktop landscape and mobile portrait layouts, though I primarily designed with the mobile experience in mind.

ChessElementa is a Progressive Web App (PWA)—an application that “looks like an app, feels like an app, but is fundamentally a webpage” capable of running offline. It relies solely on the web browser on your computer or phone, so the upside is that it “runs anywhere”:

- Users can “install to home screen” via their phone or desktop browser, effectively turning it into a full-screen standalone app

- The app can be wrapped into an Android/iOS/PC application using the OS’s built-in browser engine (WebView)

- It can also be bundled together with an open-source browser into a fully self-contained standalone application. This is more common on PC (Electron), but inflates the package size by 50–100 MB

ChessElementa itself is only 7 MB, so the Android version uses the second approach.

This project gave me a firsthand understanding of why many developers champion web-native apps. For small-scale apps and games, the first approach actually offers the highest development efficiency, the lowest workload, the most stable runtime performance, and seamless cross-platform support—with a UI experience indistinguishable from a native mobile app. Yet virtually nobody does it. The web is open; access is entirely in the user’s hands and can’t be controlled by traffic gatekeepers, which means there’s no money to be made.

Android Adaptation

“A shell app that calls the Android system’s browser engine” sounds simple enough, but the development and debugging process is considerably more involved than pure web development, with countless niggling details.

Converting a web game/app to Android typically involves using the Capacitor framework as a bridge to access phone system features: adapting to the status bar (top bar), navigation bar (bottom bar), the back button (ideally consistent with the browser’s back behavior in the web version), haptic feedback (ideally consistent with the mobile web version), splash screens, and so on. Unlike web development, these features must be built and pushed to a phone or Android emulator through Android Studio IDE—no more writing a line of code and seeing instant results with a browser refresh. To make matters worse, my web development environment WSL (Windows Subsystem for Linux) and my Android development environment (Android Studio installed on Windows) are separated by the OS, so the debugging workflow became:

Write code in WSL ->

Capacitor packages to android/ directory ->

Copy entire directory to Windows filesystem ->

Android Studio Build & Run ->

Wireless debugging on phone

Workable, just slower iteration. But what should be the efficient route for small-scale cross-platform app development—the “shell app” approach—carries heavy historical baggage in China.

As mentioned, these shell apps rely entirely on the Android system’s built-in browser engine, WebView. This engine is separate from the Chrome/Edge/Safari browser on your phone and updates independently via Google Mobile Services (GMS). The problem is, for obvious reasons, domestic Chinese Android phones have almost universally removed GMS—that is utterly useless in China! So while your browser gets promptly updated to the latest version through domestic app stores, the WebView on some phone manufacturers’ devices stays stuck at the version that shipped with the original Android OS, while others lag behind to varying degrees. And that’s before you factor in all the custom-modified WebViews in China’s complex Android ecosystem. Whether installed via APK directly or run in certain platforms’ sandboxed environments mentioned later, shell apps will invoke the system’s built-in browser engine. This means some newer HTML/CSS features and syntax simply won’t work on these phones, requiring extensive defensive code to ensure backward compatibility with versions from years ago.

And all of this only dawned on me after launching on TapTap, when I started seeing negative reviews about the game failing to launch and did some digging. Of course, the complexity of the Android ecosystem extends far beyond WebView—it’s just that shell apps get hit particularly hard. Nearly all the negative reviews ChessElementa has received so far are related to “won’t open.” By rough estimate, at least 5% of users are unable to successfully launch the game due to Android version issues.

My ultimate approach was: for relatively simple fixes, I patched them for backward compatibility; for anything that would require major surgery, I didn’t bother—instead, I detect the user’s WebView version and show a prompt, rather than letting them stare at a frozen splash screen with no explanation.

Publishing Platforms

Below are the mobile game distribution platforms I looked into. I’ve highlighted the parts of each process that are particularly troublesome or at least worth mentioning. (I don’t play many mobile games and have never published an app before, so these are probably common knowledge—but they were all news to me.)

Domestic (China)

The overarching premise: paid games require an ISBN-equivalent license number (“版号”), whether the payment is upfront or via in-app purchases. Individual developers have essentially zero chance of obtaining one. The discussion here covers only free games—free games with ads are treated virtually the same as free games in most cases, but there’s no clear legal distinction yet, and this may change in the future.

- WeChat / Douyin / Bilibili Mini Games: “Mini Games,” like “Mini Programs,” are closed ecosystems that evolved from the original “HTML5 Web App” concept. However, most of these platforms don’t accept apps built with traditional HTML/CSS; instead, they use a dedicated renderer to execute JS. Converting a finished Web App into a mini program/mini game requires significant effort in UI/API adaptation—a deep rabbit hole I chose not to go down. If you’re planning to publish on these platforms, you should start with a game engine like Unity or Cocos that integrates with the domestic ecosystem and can export directly to mini game formats, or use an open-source JS game engine like Phaser. Publishing a mini game/mini program requires a Software Copyright Registration Certificate (“软著”) and an MIIT ICP Filing (“备案”).

- There are two types of software copyright certificates: the official one from the National Copyright Administration (free; takes one to three months; guide), and a third-party electronic copyright certification (a few hundred RMB; one to two weeks; guide). Note that the National Copyright Administration’s website is only accessible from within China, so overseas developers need to VPN into the country. The required materials themselves aren’t complicated. I applied for the latter but never ended up needing it (see the TapTap section). That said, I’ve heard that acceptance of third-party certifications is gradually tightening.

- The ICP filing process typically takes 1–3 weeks. Most platforms provide a unified portal for submitting filing applications (e.g., WeChat), or you can complete it yourself on the MIIT-designated website for your registered province. If your game has online features, the server must be hosted within China, and you can file through a cloud provider (e.g., Alibaba Cloud). After submitting, you must keep your domestic phone powered on, because you’ll need to reply to a verification SMS from the MIIT within 24 hours—otherwise your application gets rejected.

- Huawei / Xiaomi / Oppo App Stores: Publish directly as an Android gaming app. Xiaomi and Oppo stores don’t support individual developer registration, so if you want to self-publish, Huawei is the only option. Listing an app on any domestic app store also requires a Software Copyright Certificate and ICP Filing; for gaming apps, there’s an additional requirement: integration of a Minor Protection (Anti-Addiction) System (“防沉迷”).

- The anti-addiction system is essentially a real-ID verification system for players (which also restricts play time for minors). It should be obvious that individual developers can hardly meet these qualifications. Mini games don’t require anti-addiction because they can only run within their host platform, which already enforces it through platform account-level verification. Android apps, on the other hand, can be downloaded and used locally, free from such constraints. Huawei’s app store provides the Huawei Game SDK, which allows Android games to perform anti-addiction verification through users’ Huawei accounts.

- TapTap: A dedicated gaming app store supporting PC and Android game downloads, as well as running select supported games directly within the TapTap client (desktop/mobile). The advantage here is that by offering “open beta play” within its own app, TapTap treats single-player free Android games as “playable demos” rather than officially published software or online services. This means the actual listing process requires neither a Software Copyright Certificate nor an ICP Filing. For games that run within the client, since users must log in with a verified TapTap account before launching, the games themselves don’t need to integrate a separate anti-addiction system either. I noticed TapTap also has a “Mini Games” section, but those games require an ICP filing regardless of whether they’re online or offline. Clearly there’s a subtle gray area here. In any case, TapTap is a very indie-friendly platform.

- ChessElementa is free and single-player, and I chose “launchable only within TapTap,” so all the hassle was avoided.

International

No license numbers, software copyrights certificate, ICP filings, or anti-addiction systems.

- CrazyGames / Poki / itch.io (Web Game Platforms): Bona fide HTML5 web game platforms. Aside from itch.io, which is basically a site only game developers visit, the other two are sizable commercial platforms. They review, run trial periods, screen, and only retain games with strong metrics and profit potential, then allow developers to integrate their ad systems and receive revenue shares.

- I gave CrazyGames a try—the upload process was very quick and convenient. Of course, ChessElementa is based on Chinese chess (Xiangqi), which presents a cognitive barrier for Western players accustomed to international chess, so the trial performance was predictably underwhelming.

- Google Play: The official Android marketplace. A one-time $25 fee to register as an Android developer; listing itself is free. The documentation for the publishing process is very clear, but there’s one addition since late 2023 that has drawn widespread criticism from indie developers: the “at least 12 testers for a 14-day closed beta” requirement.

- This requires at least 12 Google accounts to download your closed beta app and keep it installed on their phones for at least 14 days. It’s Google’s blunt instrument for filtering out low-quality apps from being listed willy-nilly. Besides asking friends and family for help, I also used an indie developer mutual-help service specifically designed for this process (website link; no affiliation, just for reference), which ensured active engagement throughout the 14 days. Beyond this drawn-out process, everything else was fast—the review between the closed beta and the actual listing took only one day, and it was on a weekend (official docs say up to 7 days).

- Google Play is very unfriendly to indie developers: it doesn’t push new releases, and its search and recommendation algorithms weigh historical download volume heavily. So newly listed “cold start” apps get essentially zero traffic.

- Apple App Store: Apple’s official marketplace. Legendarily the platform with the most traffic and highest revenue. Requires an annual $99 fee to maintain Apple developer status. Since building/debugging iOS apps requires a Mac, which I don’t own, and App Store reportedly dislikes web app wrappers, I didn’t consider it. Oh, and one more reason: I’m an Apple hater.

- Steam: You could, of course, use Electron to package it as an exe and put it on Steam, but listing a game on Steam costs $100 upfront. Plus, the Steam player base is notoriously hostile toward web/mobile games, and ChessElementa is a mobile game through and through. The in-game level editor and community cloud levels would actually fit the Steam Workshop ethos nicely, but it wasn’t worth the hassle.

In the end, I went with TapTap—the only hassle-free option in China—and Google Play for international distribution.

Aside

This little project has been quite fun. While designing the puzzle levels, I already had plenty of enjoyment from my battles of wits with the auto-solver: from “What the hell, how can there possibly be a 3-move solution for this level?!” to “Oh.”

After launch, some players uploaded levels they’d designed themselves, and some of them are incredibly ingenious—truly impressive, and they cost me quite a few brain cells. My previous work was on narrative games, where “being a genuine player of your own game” was never really possible. This has been a genuinely delightful surprise.