Written in Chinese, translated by Claude Sonnet 4.5.

People always ask “What kind of game are you making?” Today, I’ll recommend three other benchmark games in the “side-scrolling narrative adventure” genre—in other words, competitive products made by my peers. These three indie games each share certain player-attracting elements with Escape Everlit (Escape for short), so some simple comparisons might help highlight the positioning of Escape.

Calling them “competitors” is really putting gold on my own face: if you happen not to have played the three games I’m about to introduce, I would 100% recommend you try them over Escape. I’m a player myself. Players don’t (and shouldn’t) care about game developers’ investment, they only care about the quality of the game itself. These three games are all mature, refined works developed by professional teams over multiple years and proven by the market. Escape, on the other hand, is just a project I, an amateur, have budgeted a year for, with its main novelty being the uniqueness of its story style. In fact, these three competitors happen to represent three completely different story styles.

These three games are Minds Beneath Us, A Guidebook of Babel, and Pentiment.

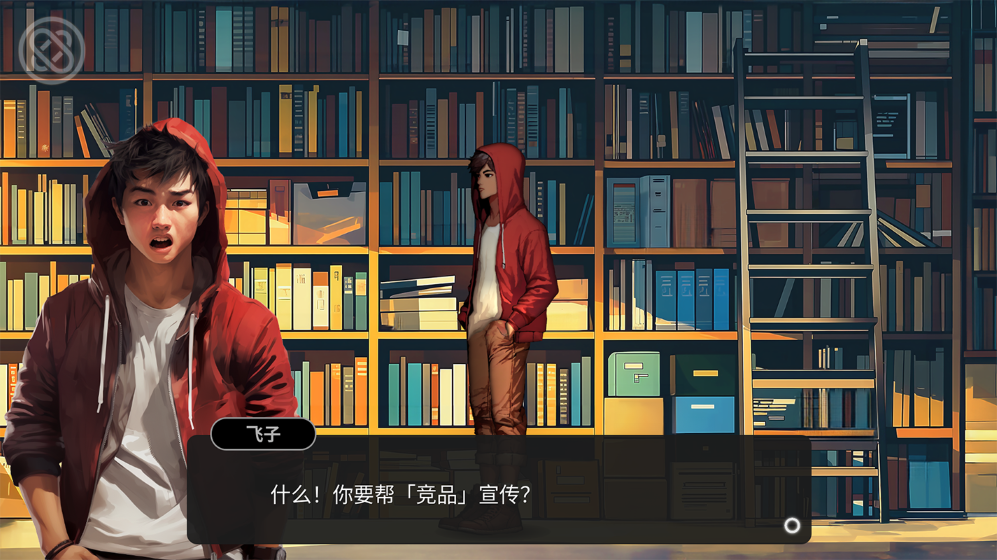

Minds Beneath Us

Made by a 10-person Taiwanese team over 5 years. Just released on Steam two weeks ago. About 11 hours to complete.

Minds Beneath Us was actually recommended to me “as a developer” by Steam. A few months ago, I started filling out the Steam store page for Escape Everlit. One item was “add game tags,” and Steam would list ten similar games based on the tags I described. Minds Beneath Us was one of them. At the time, Minds Beneath Us only had a demo released four years earlier. After playing the demo, I realized this might be the game on the market closest in style to Escape: sci-fi, near-future urban setting, Chinese-language sphere, side-scrolling text-based game, choice-oriented.

A few days ago, I finished the full version of Minds Beneath Us. The story and writing are very solid. What amazed me is that every single line spoken by the protagonist is delivered through two- or three-choice text selections, and these choices at least affect reasonable response content from NPCs. You could say the game’s immersion is largely thanks to this. The workload of writing this script is beyond my imagination… For example, in the past two weeks I spent 60+ hours writing dialogue for one level in Escape, revising over 2,000 lines of dialogue, with relatively uncomplicated branching—yet the actual gameplay time for this section is only about 20 minutes.

My favorite part of Minds Beneath Us is the “corporate worker role-playing” section: the protagonist needs to intern in two hostile groups within a tech company, navigating between power struggles and the moral implications of both jobs. Escape will have a level with a similar theme (a curator navigating various parties at an art gallery), but with much simpler character relationships than in Minds Beneath Us. In a sense, this type of plot can be called a “workplace game”—an interactive experience corresponding to workplace dramas (I’m not talking about those numerical “cultivation games” wrapped in a thin veneer of real life). This professional process easily places players in a seemingly ordinary environment, but once immersed, they realize their actions have far-reaching consequences, requiring careful consideration. Using cyberpunk as a suspenseful stimulant, Minds Beneath Us has a pretty good grasp on balancing trivial work tasks with coherent gameplay.

The biggest problem with Minds Beneath Us might be that its overly formulaic main storyline has created a ceiling for its plot development. Cyberpunk, dystopian tech companies, human exploitation… these are all concepts that have been worn out by predecessors. The advantage of formulas is that they can quickly move the plot from one state to another desired state without causing too much awkwardness or resistance from the audience—because they’ve seen it all before. But formulas are just a means; once they become the backbone, they change the quality of an independent work. Minds Beneath Us puts tremendous effort into “correcting” the blunt stereotyping of formulas through narrative text, such as throwing out smokescreens like “the company’s new technology might not rely on exploitation,” or seasoning certain very typical decisions with the protagonist’s selfish intentions. But the problem is that none of this shakes the extremely standard final ending trajectory. And other novel plot elements neither affect the game mechanics nor receive good explanations.

A Guidebook of Babel

Made by a 5-person Shanghai team over 5-6 years. Launched on Steam and Switch in August 2023. About 12 hours to complete.

A Guidebook of Babel was recommended to me “as a player” by Steam. Babel’s art style is very unique, at first glance seemingly worlds apart from Escape, but their core gameplay is very similar: multi-threaded narrative pushed forward by four protagonists. Babel features “butterfly effect” puzzles, where one protagonist’s action at a certain moment in the past affects other protagonists and themselves at later moments, tightly linking the four protagonists’ stories. Escape will also rely on four protagonists’ different behavioral styles and abilities, investigating the same scene differently through replays to mutually change their respective decisions.

I’ve always felt Babel is a refined indie game that regrettably didn’t receive the number of positive reviews matching its quality. Its absolute strength is in art: a unique fairy tale painting style with rich, smooth animation and UI design—after all, Babel’s main creator is a professional animator. Paired with the unique art is a plot highlight: an original fictional world. The game’s setting is that after humans die, they become flying fish in the sea, then are caught by Cygnians on the “Babel” ship, who help them achieve “post-death peace,” erase past life memories, and embark on new journeys. Overall, although Babel looks like a fairy tale and its dialogue and plot are light and cheerful, the story core it handles is very mature, such as various people on the Babel ship reacting differently to the fact of having died.

But this game appears somewhat buried, perhaps precisely because of the rare pairing of its art style and story setting, making it very dependent on players’ personal preferences: players attracted by the light, cute cartoon style might be confused from the start by the detailed worldview and the characters’ behavior logic consistent with the strange world; while players who like novel stories and settings might not buy this rare art style. Babel’s creator shared that his development motivation came from a personal experience, roughly about a foreign elderly couple who saw the creator’s daughter and thought she looked like their deceased little daughter and wanted to buy her something. So as a professional animator, his reason for entering indie game development has strong personal character. From a certain angle, this is similar to my starting point for making Escape: this game must be one I myself like, so it won’t “cater to demand” in important places. In any case, I congratulate Babel’s production team for producing a great game with personality.

Pentiment

Made by a 13-person internal Obsidian team over 4 years. Launched on Steam and Xbox in November 2022. About 12 hours to complete.

Pentiment technically can’t be considered an indie game, after all it’s Obsidian, acquired by Microsoft in 2018, with very ample promotional and various resources. But the main creator proposed this concept back in 1992 while working at Black Isle Studios, only successfully pitching it in 2018 with two people, later expanding to 13 team members—this process is quite “indie flavored.” Pentiment’s story theme is even more niche: a religious manuscript illuminator from Nuremberg experiences and solves multiple murders spanning 25 years in a monastery near an Alpine town. Most of the time in this game, you control the artist experiencing authentic 16th-century European life in the town, discussing various theological and Reformation details with priests, and slowly aging with the villagers. The main creator has a history degree and positioned Pentiment as a historical game.

Pentiment can be called a work of art. The game recreates numerous 16th-century European religious art styles and life details, adopting a manuscript illuminated illustration style for the game’s art, with the protagonist sleepwalking through scriptures and conversing with saints, many NPCs having their own unique handwritten or antique print fonts for dialogue boxes, etc… In narrative, it’s as restrained as monastery life, focusing on depicting the credibility of town life and characters, as well as the various inner turmoils of the devout artist, so players can perceive the impact of their words and actions on others when solving murders. For example, the consequences of accusing different murderers are revealed seven years later.

It’s hard to say what flaws Pentiment has. I myself am not a history or theology enthusiast, nor am I interested in European religious art. But this game made me enjoy this “twenty-five years as one day tour of the monastery” through solid experience and details. I think this is the highest level of narrative experience: even if you’re a player/audience uninterested in “a certain type of plot” or simply an overly personalized story lacking commonality, you’ll inevitably respect and ultimately immerse yourself in the story due to the authentic weight brought by the narrative. Because players feel extremely strong vitality or organic complexity—and then, out of human curiosity, can’t help but explore seriously.

Conclusion

Although I only recommended three so-called “competitors,” there are many similar games that have given me incomparable experiences. One of the greatest gains from developing an indie game is being able to empathize more with the vast amount of effort invested behind these works that have let me live many other lives. After 30+ years as a game consumer, I hope Escape Everlit can “give it back” in some sense.