Written in Chinese, translated by Claude Sonnet 4.5.

This article consolidates multiple development logs from July to September 2024, originally used for social media promotion. Archived here for the record.

Preface

Over the past eight months, I’ve been independently developing a game: Escape Everlit.

Today, the free demo version of the game launched on Steam!

For those interested in narrative games, you can visit the Steam store page to view the trailer and other details, or download the demo directly. The demo takes approximately 90-120 minutes to complete, including the prologue and most of the first level “Qinghua Pool Subway Station”; you can play as two of the four protagonists. The demo gives you a taste of the overall story style and general gameplay of Escape Everlit. This is the type of interactive narrative game meant to be savored slowly. The demo contains just over 50,000 Chinese characters.

The story of Escape Everlit takes place in China in 2042. Four protagonists of vastly different ages, professions, personalities, and ways of thinking were just moments ago in the heart of a metropolis, but now find themselves inexplicably in a strange island villa surrounded by endless ocean. To return to their original lives, they must use their respective strengths to uncover the cause behind this “crossing incident.” Not everyone will be able to return to their former life—your decisions are an indispensable part of this unique story.

This is a game that simply wants to tell a good story. Players will [walk and interact with the environment] + [engage in dialogue choices with various characters] to figure out [what exactly happened] and [what should I do]. That’s it. If the plot makes you feel “I didn’t see that coming” while also feeling “but it makes perfect sense,” then I’ve achieved my goal—to write science fiction and mystery stories that are interesting and believable.

At the same time, this is also a story that can only be told through the medium of games. [Character switching] is the core mechanic: players need to operate and combine the different approaches of each protagonist, trying various possible actions to smoothly progress through story levels. Each different choice brings new discoveries. (Due to story presentation requirements and length limitations, this mechanic isn’t fully demonstrated in the demo.)

After playing, whether you have positive or negative feedback, you’re very welcome to leave a review or thoughts on the Steam store page for the Escape Everlit demo (or right here), and I will respond earnestly. This is my first time making a game, so I lack experience—please provide feedback to help me learn how to do better. The game’s subsequent chapters and levels are still in development, so your feedback will influence my development direction and story creation.

OK, ad over. But you might have some other questions, like “Why did you suddenly start making a game on your own?”, “What exactly did you do in these eight months?”, “How much does making a game cost?”, “What genre is your game?”. Well, below I’ll discuss the story and data behind making this game.

Why Make a Game?

Eight months ago, I was still an “AI scientist” in tech industry, working on solving various practical problems in the tech industry using statistical and machine learning methods. I knew nothing about making games: I never received systematic software engineering training (statistics/math-related degree; mainly used Python/R at work for models and data analysis), hadn’t touched artistic skill trees like drawing, 3D modeling, or music, and naturally didn’t understand more specialized techniques like numerical planning, level design, or scriptwriting.

So how did I have the audacity to quit my job and start making a game on my own? Here’s the thing: I’m a player with over 30 years of gaming experience, and throughout these eight months, and until the day Escape Everlit releases, I’ve been playing a very interesting game. This game has only one platinum trophy achievement:

Can you make a game of decent quality on your own within a year?

I mainly play action, adventure, puzzle, and RPG genres. I’ve marked about 300 games on Douban and feel my standards for judging games aren’t low. I’m not naive enough to think making a good game (or making anything good) is easy, and I did my research on indie game development cycles. (However, like many first-time indie game developers, I had to multiply my time budget by two midway… initially planned for six months.)

So, this achievement’s completion condition is full of challenge, arousing my fighting spirit to test whether a good gourmet can be a good chef.

Another motivating factor was the increasing maturity of generative image AI. The medium of video games can be said to carry 50%-99% of its content visually, and I have no artistic skills. Most players probably share the dream of making their own game, and technological development has happily made this dream possible for the first time. My career, in plain terms, has been “building AI models with data to achieve or optimize a certain goal.” This “goal” is generally to offer a user new experiences or enhance their existing ones. I’ve designed and applied AI for many individuals or departments who needed help, and this time, I’m the user, completing my own goal.

A large part of the fun of games lies in learning—such as familiarizing yourself with rules, testing strategies, exploring new interaction patterns. The “full-stack” skill tree required for making games forced me to venture into a vast array of new fields over the past six months: game engine (Godot), 2D animation (Spine), image editing (Photoshop), sound adjustment (Audacity), trailer production (DaVinci Resolve)—although I’ve noted the tools I used for reference, the truly difficult and interesting part isn’t learning to use the tools, but understanding the design principles and logic behind these tools, i.e., the “experience” and “feel” that experienced practitioners have. With the “everything can be automated” perspective gained from years in the industry, I also fully tested and experienced the limitations of current generative AI in accelerating game production during this learning process—many things still require manual work to achieve a certain quality of results, even from these novice hands.

The above are my reasons for making games: I just wanted to; for fun; to learn new stuffs.

Where Did the Time Go in Making the Game?

This is truly a very time-consuming endeavor. Two months ago, when I’d been making the game for six months, I did a “midterm summary,” see the charts:

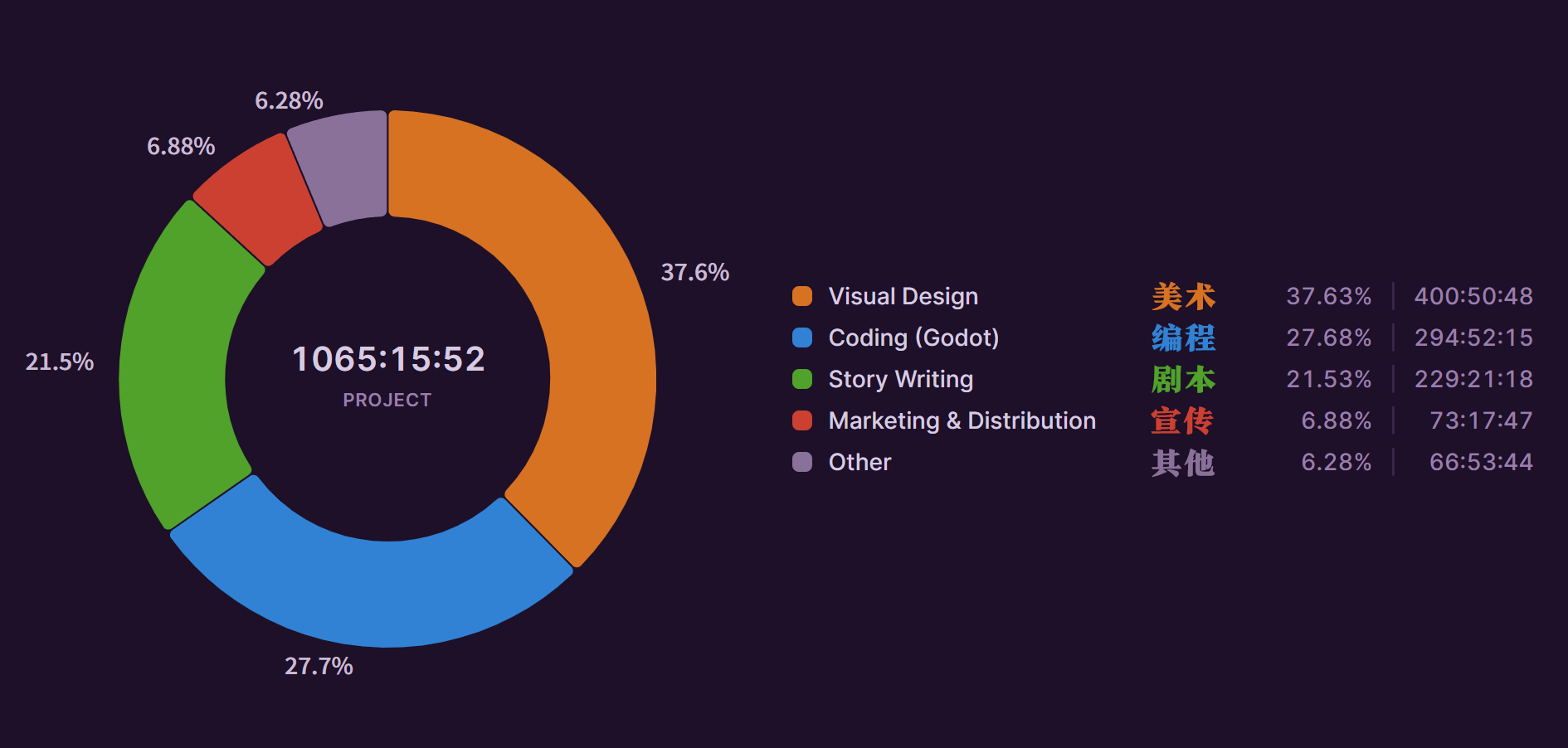

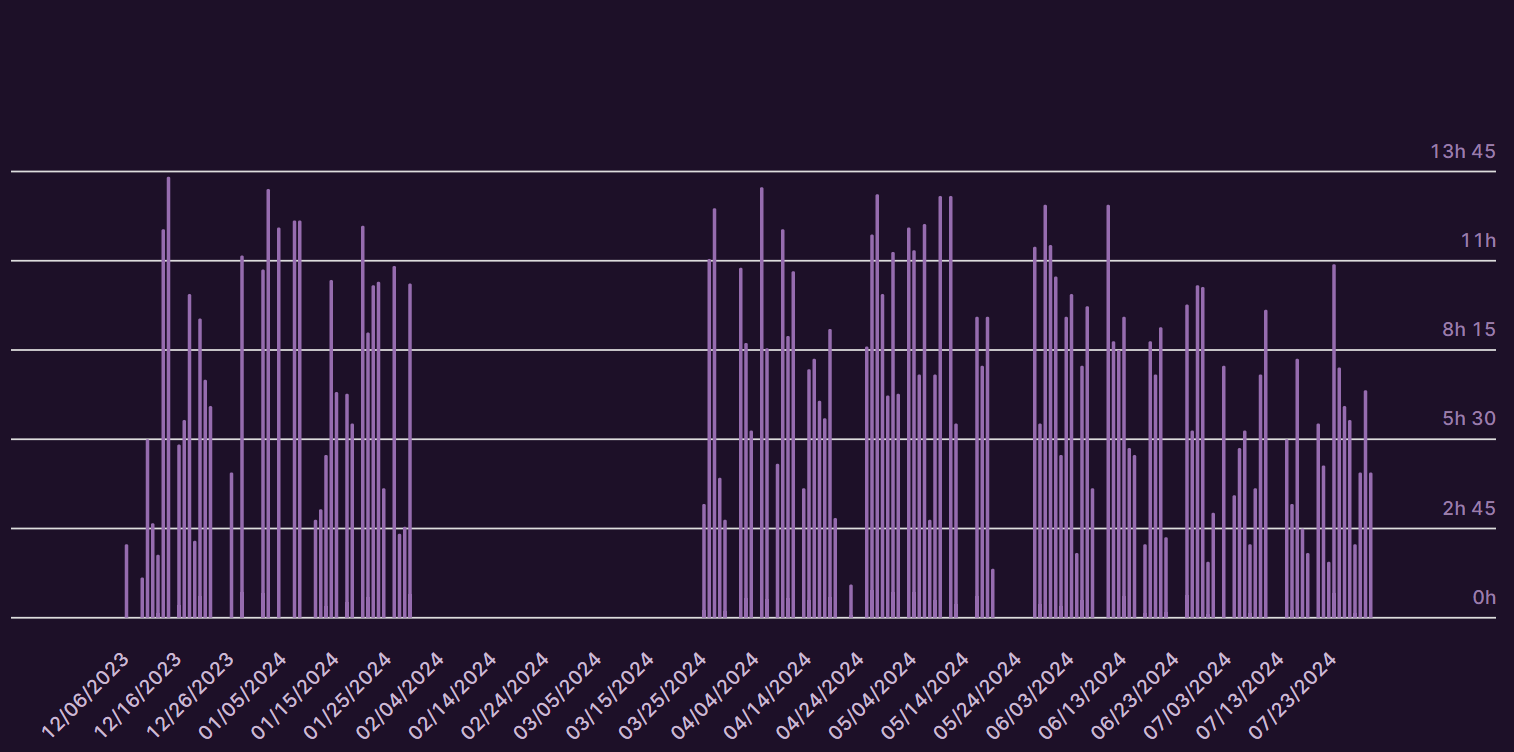

- From quitting last December to July this year, I spent a total of 1,065 hours learning and making the game, which equals 133 8-hour workdays, or 26.6 work weeks.

- As shown in the gap in the chart, from late January to late March this year, I was mainly traveling around China and eating well, doing nothing game-related except recording some environmental sound effects

- Excluding the above vacation, the average working time was almost 8 hours per day

- This data doesn’t include “competitive research,” i.e., time spent playing other games (about 270 hours…)

- These 1,065 hours were basically divided equally among “Art,” “Programming,” and “Script”:

- “Art” 37.6% - AI-generated original images, Photoshop editing, skeletal animation, shader visual effects, visual-related level design, etc.

- “Programming” 27.6% - Any editing work in VS Code and Godot GUI, and non-script related coding

- “Script” 21.5% - Story outline, character design, dialogue and cutscene design, story-related level design, etc.

- “Marketing” 6.8% - Steam page/Steamworks related, trailer production, copywriting and development logs (including this article)

- “Other” 6.5% - Various miscellaneous items, mainly sound effects and AI-generated music; this belongs to post-production and currently has a lower proportion

After another two months, the total time is now close to 1,300 hours. As development progresses, time allocation has also changed; for example, scripts now account for 29%.

My partner always jokes that “you, an unemployed, actually ends up working more hours on average than when having a proper job.” That’s right—at work, at least 2/3 of the time is spent on verbal communication (meetings) and written communication (reading and writing presentation documents). But these eight hours of making games are solid “constructive work time,” and completely my own time. Don’t get me wrong, communication in teamwork is appropriate and necessary; but that doesn’t prevent one from yearning for ideal work without ineffective communication, right?

Where Did the Money Go in Making the Game?

No, no, making games doesn’t cost money, it just takes time and prevents earning other money… A month ago, I also did a spending statistics: Total expenditure over seven months was approximately $1,579, or RMB 11,243. Not extravagant.

Below is a breakdown of expenses by category. This record only includes expenses directly related to game production, excluding living expenses and the opportunity cost of quitting. Since it’s solo development with no outsourcing, as expected, money was basically spent on various service subscriptions or software purchases. So, you can also view this as a “List of Generative AI-Assisted Game Development Tools/Services.”

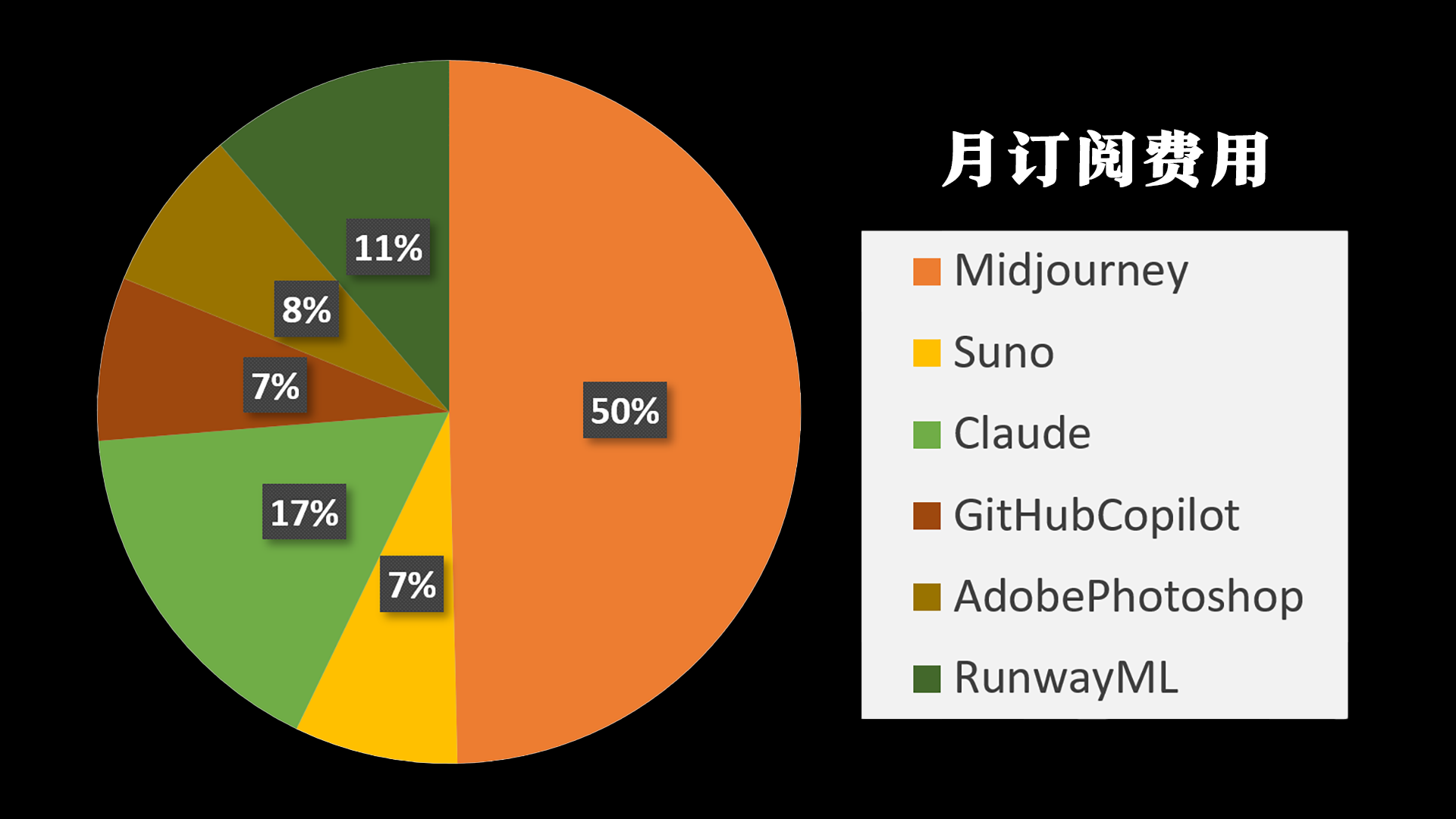

Regular Subscription Fees

Total of $122/¥870 per month; 7 months equals $854/¥6,090.

- Midjourney, Image Generation AI, $66/month

- Created all the 2D image assets currently needed for the game

- Using the $60 tier because it’s the lowest subscription level that keeps images private and has commercial license

- I don’t use open-source models, firstly for legal convenience in commercial use, secondly to avoid the time hell of various finetuning; same below

- MyEdit, Sound Effect Generation AI, $4/month (annual $48)

- Created most text-to-sound effect assets, quick to obtain and decent quality

- Apart from this, higher quality sound effects mostly come from CC0-licensed free assets on freesound.org

- Also tried its AI voice, but I can’t stand that Chinese TV drama dubbing tone, so dialogue remains “beep beep beep”

- Suno, Music Generation AI, $10/month

- Currently only used for trailer music and a few tentative BGMs

- Haven’t decided on the game’s music style yet, so this should be used more in post-production

- Claude or ChatGPT, Large Language Model, $22/month

- Wrote some encapsulated, non-core Godot code, such as sliding billboards, character query interface, etc.

- Wrote the dozen or so Shaders currently used in the game, because I really can’t find interest in learning shader code

- (Of course not just for making games; used to use GPT-4, but it’s gotten dumb, so alternating with Claude)

- GitHub Copilot, Code Generation AI, $10/month

- Only use its code auto-completion function, saving a lot of repetitive typing or formatting work

- Most useful for completing similar functions, like when I write

show_box(), it can reliably instantly producehide_box()

- Adobe Photoshop, Image Editing, $10/month (annual $120)

- Besides regular image processing, mainly use PS’s AI generative fill to locally modify Midjourney-generated assets

- Midjourney’s previous generative fill was very hard to use, but output quality is much higher than PS. PS excels at modifying simple parts of images.

- $120 is the Black Friday discounted Creative Cloud Photography annual price. Including the font library is quite cost-effective.

Intermittent Subscription Fees

Total of $75/¥535.

- RunwayML, Video Generation AI, used for two months, $15/month

- Currently used it to trial-make two title screen animations and one cutscene animation. Will use it intensively again during later production stages.

- Runway Gen-3 is much higher quality than before, but $1 for 10 seconds (the $15 subscription only gives you 40 seconds, need to buy extra credits)

- Adobe Illustrator, Vector Graphics Editing Software, used for two months, $22/month

- My family member used it to create the Lantao LOGO and merchandise (yes, we now have various stickers, fridge magnets, and other non-sale merchandise)

- Two months because I forgot to cancel the subscription after the first month…

One-Time Payments

Total of $650/¥4,640.

- Steam APP Registration Fee, $100

- Protection money paid to Steam

- Spine 2D Professional, 2D Animation Software, $370

- For skeletal animation. Lifetime purchase, very convenient and easy to use

- Spine Sample Character Animation Asset, itch.io, $20

- Referenced someone else’s assets when learning how to do realistic human skeletal animation, not actually used in the game

- Dialogue Sound Effect Pack Asset, Unity Asset Store, $10

- A complete set of dialogue “beep beep beep” sounds, format and length already processed neatly, very convenient

- Competitive Research, $150

- Purchasing 2D narrative games on Steam and Switch similar to Escape from Everlit Island

No Payment (Open Source or Free)

- Godot, Open Source Game Engine

- Of course Unity and Unreal are also free, unless your game becomes a hit

- Audacity, Open Source Audio Editing Software

- Mainly for cutting length, adjusting volume, splicing, adding echo, etc.

- DaVinci Resolve, Free Version Video Editing Software

- Used for making trailers and editing videos generated by RunwayML. This thing is extremely useful and free, a blessing to the industry

Any Similar Game Recommendations?

Escape from Everlit Island roughly belongs to the “point-n-click narrative adventure” genre. I wrote a “competitive report” listing three other benchmark games of the same type:

- Pentiment

- Minds Beneath Us

- A Guidebook of Babel

You can read my separate detailed article introducing them.

Calling them “competitors” is really flattering myself: if you happen not to have played these three games yet, compared to Escape Everlit, I 100% recommend you try them instead. I’m also a player myself. Players don’t (and shouldn’t) care about game developers’ investments, but only about the game’s own quality. These three games are all mature, refined products developed by professional teams over multiple years with multiple people, tested by the market. Escape Everlit is merely a project by an amateur with a one-year budget investment, with the main novelty being the uniqueness of the story style (in fact, these three competitors happen to represent three completely different story styles).

Although I only recommended three so-called “competitors,” there are many similar games that have given me incomparable experiences. One of the greatest gains from developing an indie game is being able to empathize more with the vast amount of effort invested behind these works that have let me live many other lives. After 30+ years as a game consumer, I hope Escape Everlit can “give it back” in some sense.

Conclusion

Thank you for reading this far. Escape Everlit will be in the Steam Next Fest from October 14-21.