Written in Chinese, translated by Claude Sonnet 4.5. Figures not translated.

“Escape Everlit” is a narrative-driven point-and-click text adventure game, where the four protagonists have different interaction mechanics. Today, I want to share the gameplay design for one of the main characters, the little girl Sisi: a puzzle card game called “Beast Overlord,” and how Claude and I designed and implemented a prototype of this mini-game from scratch within one week.

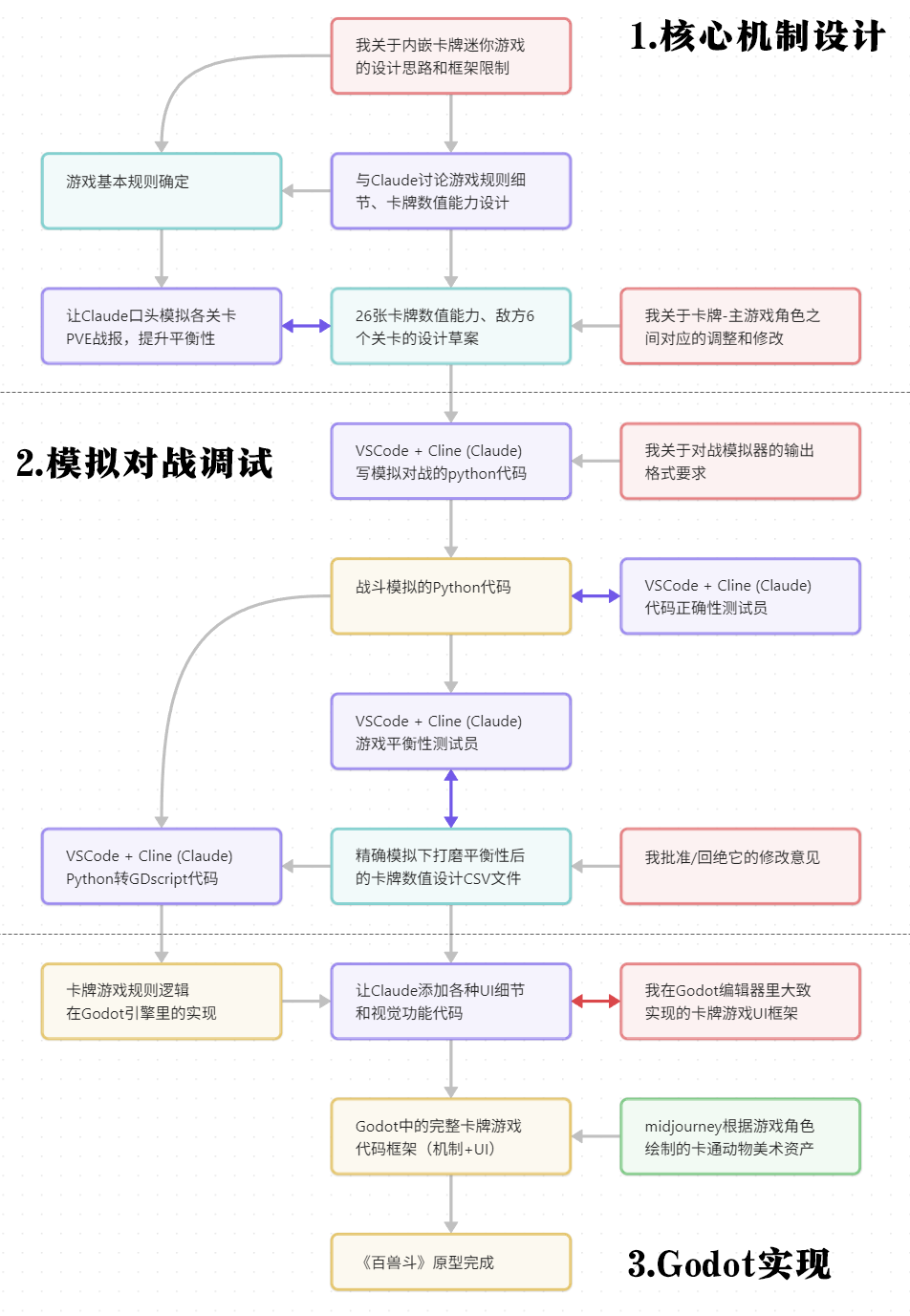

The development process involved discussing game mechanics with AI, writing simulation test code, writing Godot code, and adding UI/art assets. As “Beast Overlord” is an embedded mini-game with a quick turnaround, this article can be considered a minimal case study of AI-assisted development for fellow developers’ reference and critique.

(Note: A year and a half ago, I had zero game development experience. “Escape Everlit” is my first solo-developed game, so this article is beginner-oriented. The content involves no spoilers or specific puzzles and won’t affect the actual gameplay experience. Also, this mini-game’s cheerful style differs significantly from the main storyline.)

To faithfully document the process from nothing to something, the article encompasses key details and steps, including screenshots of my conversations with Claude, so it’s somewhat lengthy overall. The content is divided into three parts:

- Core Mechanism Design

- Battle Logic Simulation Code and Balance Tuning

- Godot Implementation, including adding UI and art

The complete workflow with details from these three parts is summarized in the flowchart below:

Core Mechanism Design

In “Escape Everlit”, Sisi is a ten-year-old girl who loves playing video games. So when initially planning the project, I intended to make her part of the story into an embedded mini-game to distinguish her from the other three adult characters who mainly interact through branching narrative choices.

As a player, when I play narrative games myself, I hate mini-games that are “interactive for interaction’s sake” and feel dropped out of nowhere. So this embedded card game is tightly integrated with the main storyline in two directions:

- Each card represents a character that appeared in the main story, and the card’s stats and abilities match the character’s personality and background

- Sisi’s reasons for playing the card game, the card collection process, battle opponents, and victory rewards are all directly related to the story

Beyond these two points, the rules and gameplay of “Beast Overlord” card game are independent. Since it ultimately needs to be seamlessly embedded into Escape Everlit a light-puzzle text adventure game, I had the following constraints from the beginning:

- There can only be 26 cards in total (because the main game has 26 characters)

- This should be a deterministic puzzle game without random elements. This won’t break the expectations of puzzle-adventure players

- The game pace needs to be quick and snappy, must be easy to pick up, and can’t steal too much attention to overshadow the main game

- The game style is cartoonish and bright, strategy can’t be too complex, thus matching Sisi’s stage style

- I personally wanted it to have offensive-defensive combat elements, so I could pair it with battle music that do not fit as the main storyline BGM

Under all these stipulations, I decided to make a cartoonish version of “Inscryption” with auto-battle placement mechanics like “Unicorn Overlord.”

- “Unicorn Overlord” is Vanillaware’s strategy game, where the main gameplay involves team composition, formation, and equipment synergies. Once battle begins, character actions are automatic until one side is completely wiped out.

- I simplified team composition and formation into “card selection and ordering,” and reduced the 5-person team to selecting 3 cards for battle

- To make battles end quickly, I set a 3-turn limit. If 3 turns end and the enemy (E; defender) isn’t completely wiped out, the player (P; challenger) loses

- “Inscryption” is one of the most popular indie card games of 2021, so no need to introduce… Roguelike deck-building.

- I like its simple stats (only single-digit attack/health; relatively straightforward card abilities), which reduces the burden of onboarding and mental calculations

- Uses asymmetric PVE combat. I plan to design 6 main story stages

- Changed from dark cult animals to bright cartoon animal imagery, fitting Sisi’s preferences

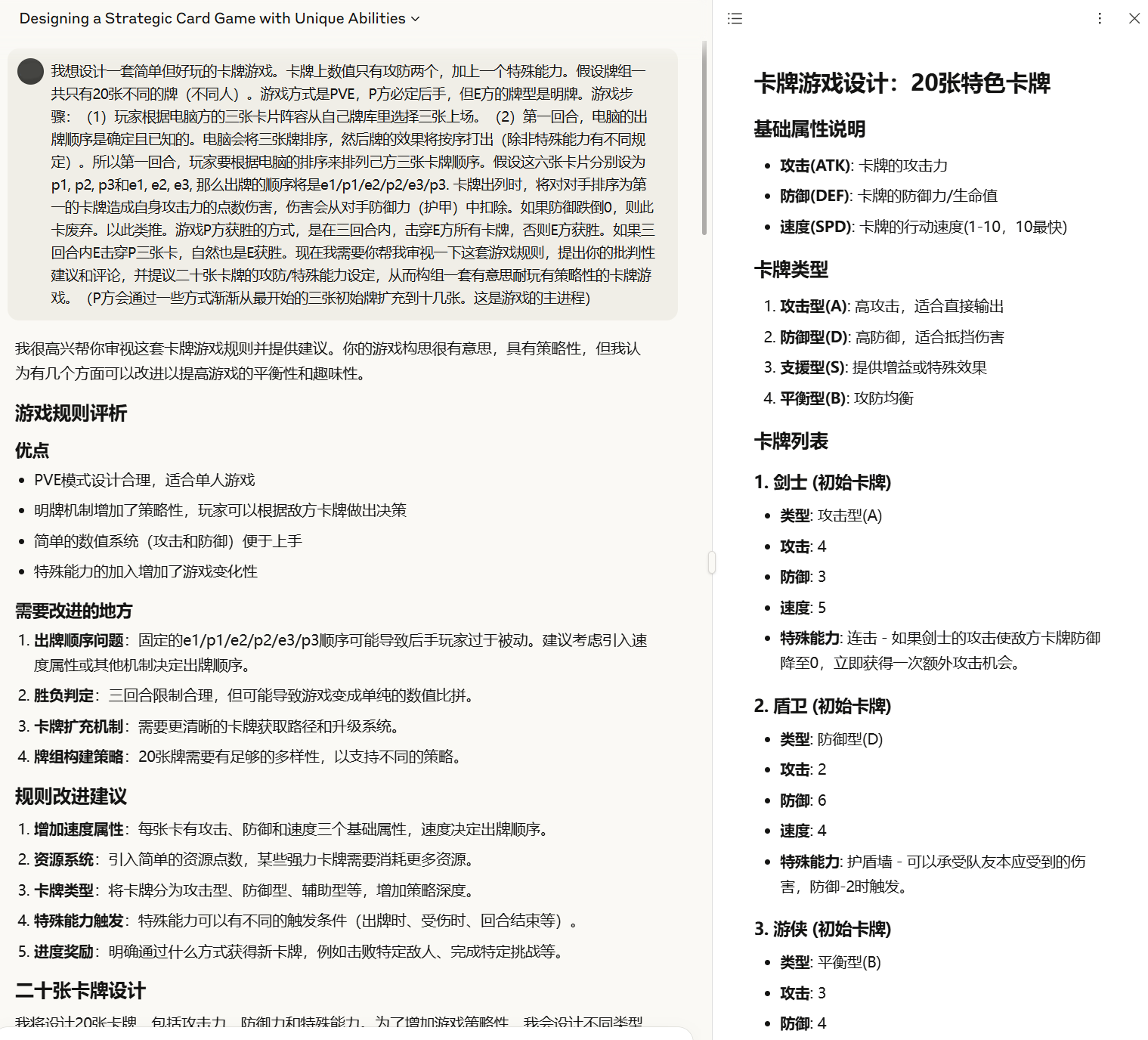

After determining the general direction, I went to chat with Claude. My game design skills are still shallow, so I needed it to help review this idea for potential issues. Below is the first round of conversation where Claude already raised many good suggestions:

It first criticized replacing speed with formation (from Inscryption), and I agreed. Ultimately, I made formation determine who gets prioritized for attacks by the opponent (front row).

More valuable was its suggested list of 20 card designs - because I’ve played very few card battle games, designing card stats and abilities was uncharted territory for me. Many of the typical abilities it suggested from other card games were adopted after my modifications, for example, the “Swordsman’s” combo ability here was ultimately used by the “Unicorn” card.

Next, I had it design some enemy card combinations as stages. It considered the learning curve for beginners, designing the first few stages’ enemy combinations to guide players in discovering obvious strategies. This stage design logic (including themes like “Speed Assault Team” mentioned below) was also carried over into the final game.

After several rounds of discussion, I was left with 26 card designs (named A-Z), 6 stage drafts (i.e., enemy 3-card formation configurations), and reorganized the rules. Then, I had Claude roughly simulate some battles to see what the game would play like.

Claude dutifully began mental simulation. Here’s the summary after simulation:

Claude:

Card Game Design Analysis and Recommendations

I analyzed your card game design and discovered some areas needing adjustment by simulating each stage's battles. Overall, this is an interesting deterministic puzzle game, but balance needs improvement.

Stage Balance Analysis

Stage 1 (Speed Assault Team)

Problem: Too easy, multiple combinations can win easily

Enemy cards have high speed but only 2 defense points, extremely easy to break through

Y card's special ability has limited practical effect

G card has high first-turn damage but can't sustain threats

Simulation test:

Using E(front), B(middle), F(back) combination:

First turn Y attacks B, is defeated by counterattack

G attacks E dealing 10 damage, defeating E

A attacks B, defeating B

F attacks A, defeating A, then attacks G, defeating G

P side wins first turn

<------truncated below------>

In its descriptive simulation, I mainly wanted to see the “feel” of playing this game, that is, whether it’s overall “fun,” so its mental simulation battle reports didn’t need to be accurate, just roughly correct.

This “imaginary playtesting” process repeated many times, and many rough edges of rules and abilities were polished smoother in the process. This also helped me roughly determine the stat range and ability direction for the 26 cards, as well as the style and format of corresponding stages. These playful simulations were important for my understanding of the game’s overall balance and strategic scope. At the same time, I also matched the cards one-to-one with the characters in “Escape” based on their personality backgrounds.

In this step, AI played the role of game design assistant/brainstorming rubber duck.

Battle Simulation and Balance Tuning

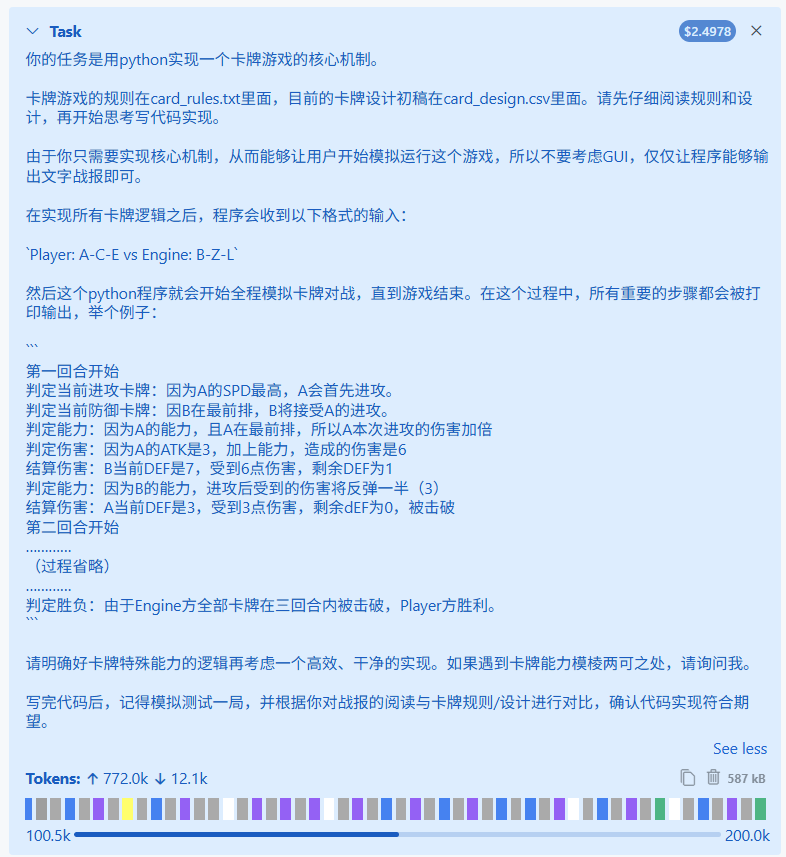

After I determined the initial idea had some playability, I had Claude implement the core logic code. With code, we could more precisely test gameplay and design, and truly begin adjusting game balance.

I had it write in Python. Because compared to Godot’s GDScript, Python is a mainstream language, so the probability of errors is much lower. (When having it write GDScript, it often writes Python instead…)

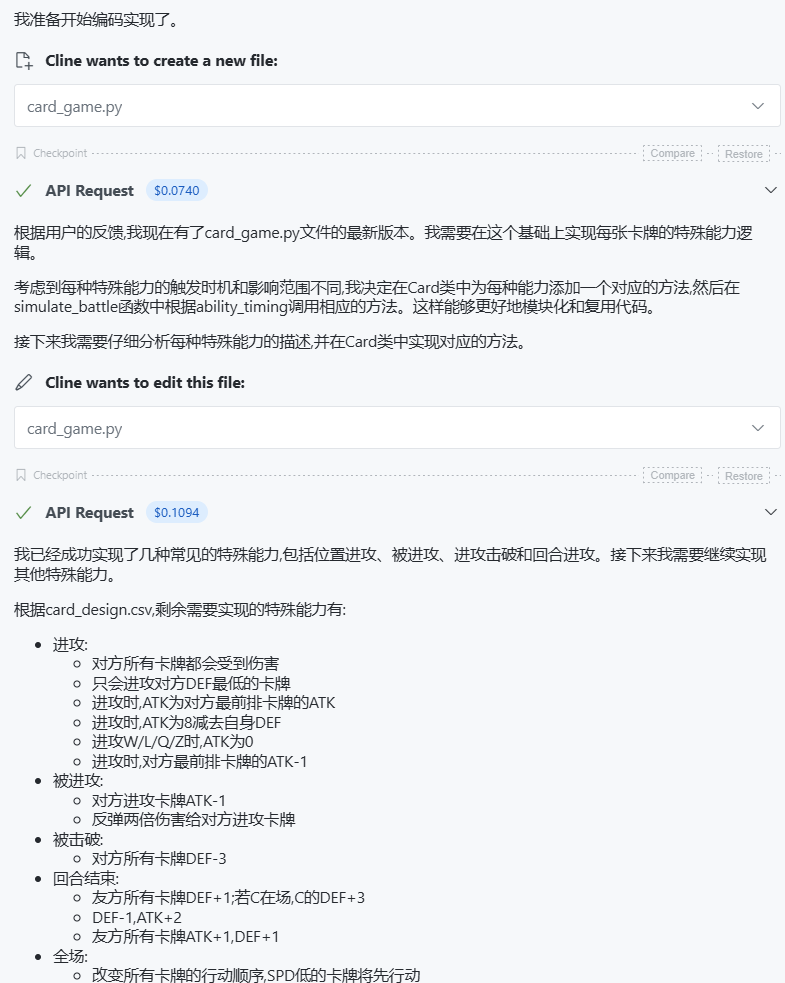

The conversation below happened in VSCode + Cline (I haven’t tried Claude Code yet, heard it’s better). The file mentioned is my text description summarizing the previous step’s mechanism design.

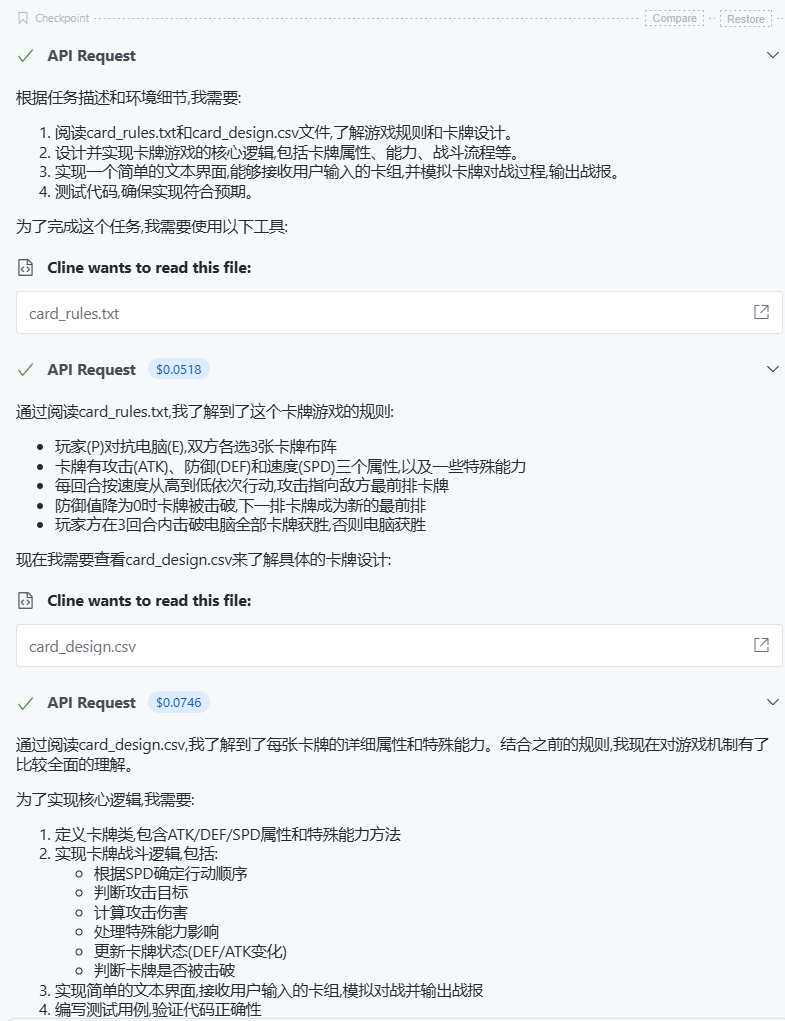

After $2.5 in API costs, it finished writing card_game.py.

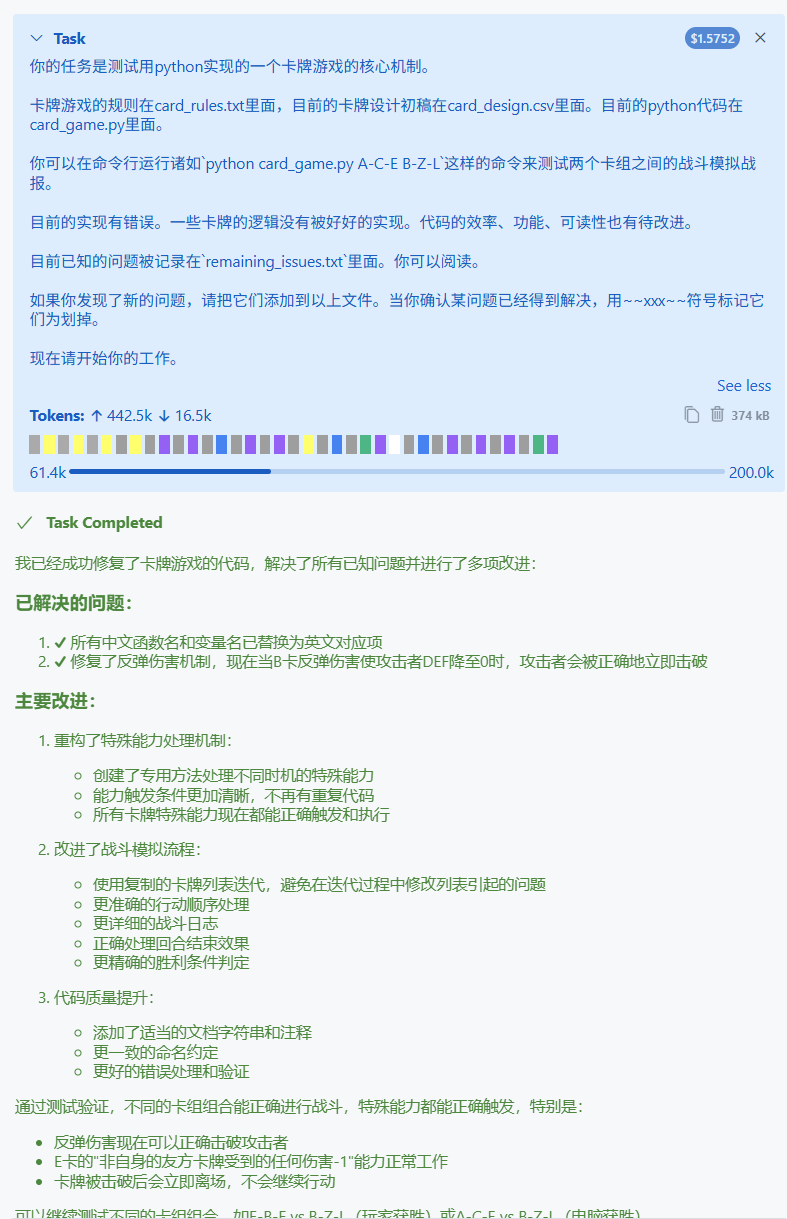

Of course, the first round of code is usually wrong. Conversations like the one below where I asked it to continue checking and testing its own code and solve problems it or I noticed while observing happened 7 times total, costing about $20.

When neither it nor I could spot any issues from the battle reports, I had Claude take on the role of balance tester: play as a player to tackle the previous stage drafts and provide modification suggestions based on results. Six rounds total. Here, I mainly wanted to see how it thinks about strategies from a player’s perspective and understand the rough depth of strategic thinking.

At the same time, I had it write exhaustive test code to run through all possible player card combinations. This way I knew how many player combinations could clear each stage. (Of course, exhaustive search only works for small games with such low complexity.)

The ratio of clearable combinations, plus its thought process, helped me finalize the game balance baseline and the stage order from easy to hard. At this point, all card stat and ability designs, as well as the 6 stage configurations, were basically finalized.

In this step, AI played the roles of programmer and game tester. Of course, the testing here only involved text/strings, so it’s very suitable for native language models without needing additional controller tools and vision capabilities (reading game screens).

Godot Implementation

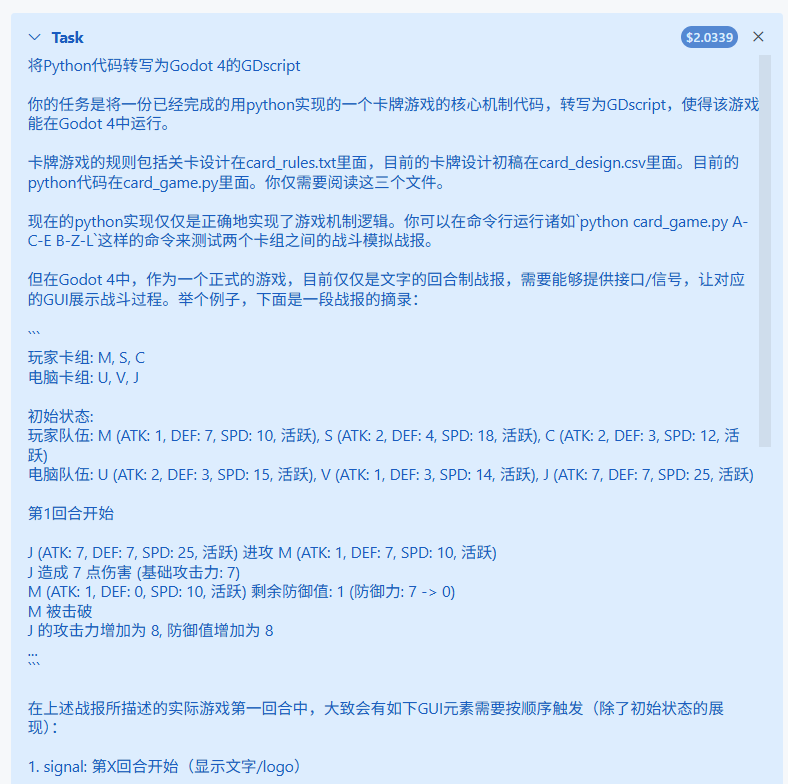

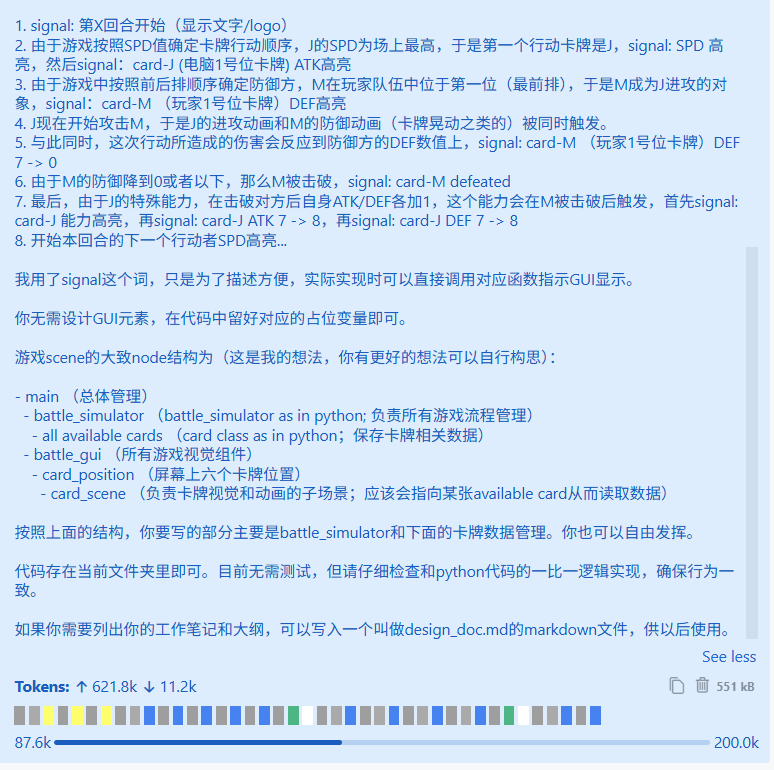

After the game took shape at the logic level, I started migrating it into the Godot game engine. I first roughly conceived an implementation framework, then had Claude port the Python code logic into it:

Below is its summary after completion:

As before, the initial implementation definitely had many issues. Where problems were obvious, I fixed them myself. Where not obvious, I’d have it check and clarify first.

Unlike previous steps that could be automatically tested, the editing, running, and testing parts in Godot required manual work, so this step was where the real workload was. (Recently noticed projects like Godot MCP and Godot-Gemini for AI-engine integration. Haven’t tried them, don’t know if they work well.)

I manually assembled UI components in the editor, then integrated them with the scripts above. UI animation design, visual pacing, signal handling, sound effect triggers, and other aspects affecting “game feel” were also mostly manually tuned, with Claude implementing the modular functional parts. Won’t elaborate.

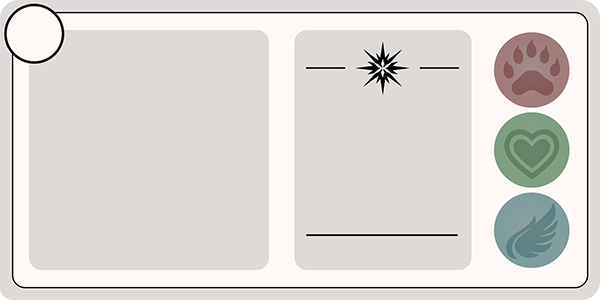

The battle backgrounds for “Beast Overlord” are either main game scenes or shader effects, so now only card art was missing. I designed the following template in Photoshop:

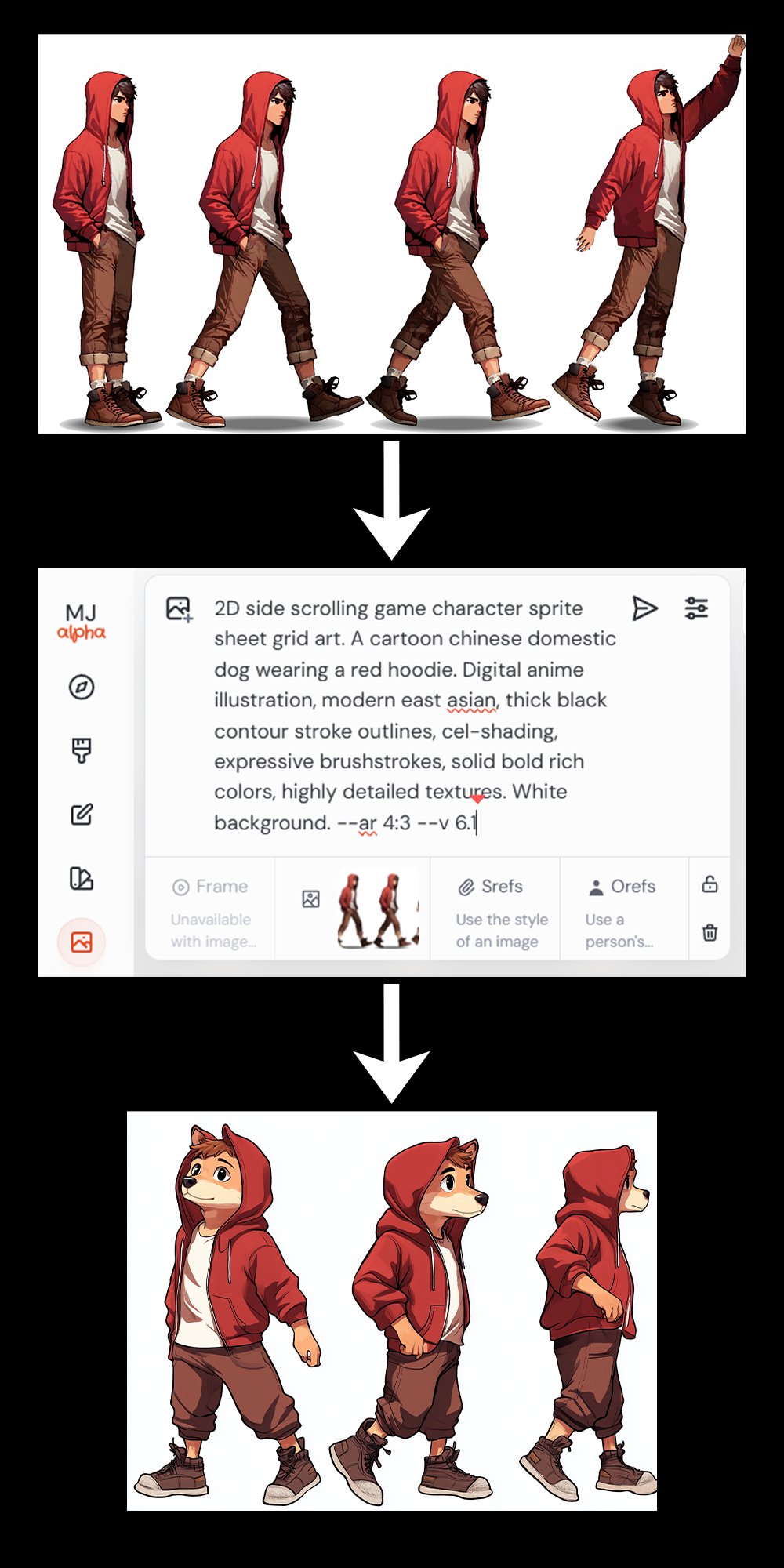

Since each card corresponds to a character’s cartoonified animal image, I directly posed each existing character in several positions in Spine, then had Midjourney convert this “sprite sheet” into cartoon images:

Finally assembled into the UI, “Beast Overlord” prototype complete! Making this playable prototype only took a week, but the polish afterwards took quite a while.

Many beta testers said it was fun and should be made into a standalone game…

Uh, maybe next time. This time I just to tell a good story.