Written in Chinese, translated by Gemini 3.

The meaning of “Wisdom of the Crowd” is simple:

- “Two heads are better than one.” — Proverb

- “It is possible that the many, no one of whom taken singly is a sound man, may yet, taken all together, be better than the few, not individually but collectively…” — Aristotle, Politics, Book III

However, a maxim is ultimately just a maxim. Regardless of which philosopher voiced it, without solid theoretical and experimental verification, it remains little more than platitudes. In the first half of this article, we will examine various methods for extracting wisdom from crowds; in the second half, we will discuss how these methods can benefit those of us living in the age of AI.

Making Humans Models

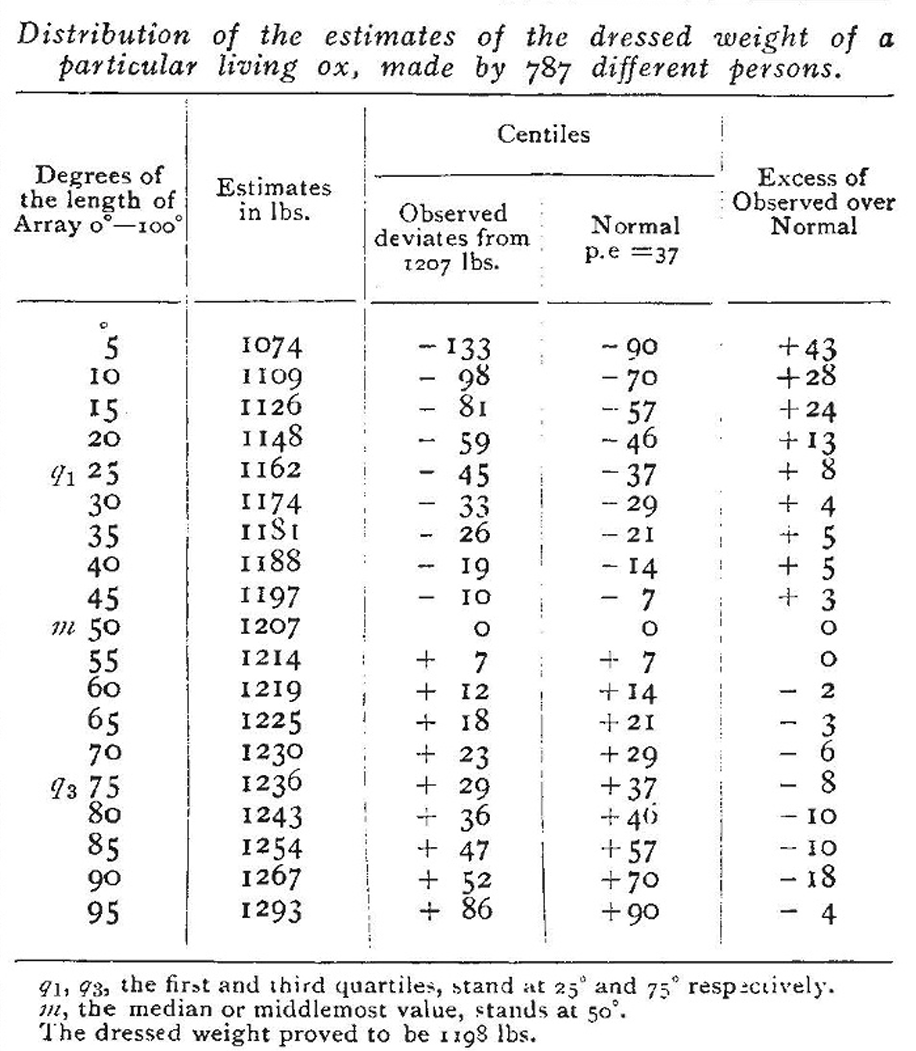

The most classic experimental data on extracting wisdom from crowds comes from a short article titled “Vox Populi” published by statistician Francis Galton in the March 1907 issue of Nature:

A weight-judging competition was carried out at the annual show of the West of England Fat Stock and Poultry Exhibition recently held at Plymouth. A fat ox having been selected, competitors bought stamped and numbered cards, for 6d. each, on which to inscribe their respective names, addresses, and estimates of what the ox would weigh after it had been slaughtered and “dressed.” Those who guessed most successfully received prizes. About 800 tickets were issued, which were kindly lent me for examination after they had fulfilled their immediate purpose.

The competitors included butchers and farmers, but also many non-experts. The median of all their “votes” (the value where 50% of guesses were lower) was 1207 pounds (547 kg), while the actual dressed weight was 1198 pounds (543 kg). The error was only 0.75%. This precision is staggering: estimating the dressed meat weight from the appearance of a live ox requires significant experience, yet this aggregate estimate managed to control the error to within one percent.

Without knowing the identity of any individual competitor, simply by “calculating the median,” we obtained an answer more precise than that of the vast majority of individuals.

The same pattern has been reproduced universally elsewhere. In the US, there is a quiz show called Who Wants to Be a Millionaire?. When contestants are stumped, they have lifelines: they can “Phone a Friend” or “Ask the Audience” (where the studio audience votes on the multiple-choice options). Statistics show that the “Phone a Friend” correctness rate is about 65%, while “Ask the Audience” sits at a staggering 91%. Considering that contestants naturally call the friend they consider an “expert” on the topic, this gap is remarkable. James Surowiecki details more such cases in his book The Wisdom of Crowds.

You can even try this right now: How tall is the Eiffel Tower? Please write down your own guess first, then randomly ask a few friends around you separately. Finally, check which is closer to the true height: your original answer or the median of all your answers combined? The correct answer can be found in the appendix of this article1.

The emergence of crowd wisdom requires two conditions: the problem’s answer can be guessed via common sense but is hard to pinpoint precisely; and the individual answers possess a certain degree of random diversity2. When both conditions are met, the crowd’s average judgment often beats the individual—even the expert.

In the field of AI (Statistics and Machine Learning), the method of utilizing crowd wisdom is called Model Ensemble: integrating the outputs of several weaker predictive models to form a stronger prediction. Model Ensemble is arguably one of the most famous “brute force magic” in the AI field. On the Kaggle machine learning competition platform, almost every champion of data modeling contests is a blended model resulting from ensembles; “pure-blood” single models almost always lose. When model performance is suboptimal, simply ensembling a few different models almost always improves the result. However, in real life, if the accuracy gain from the ensemble is marginal, it may not justify the cost of manpower and computing power required to maintain multiple distinct models simultaneously.

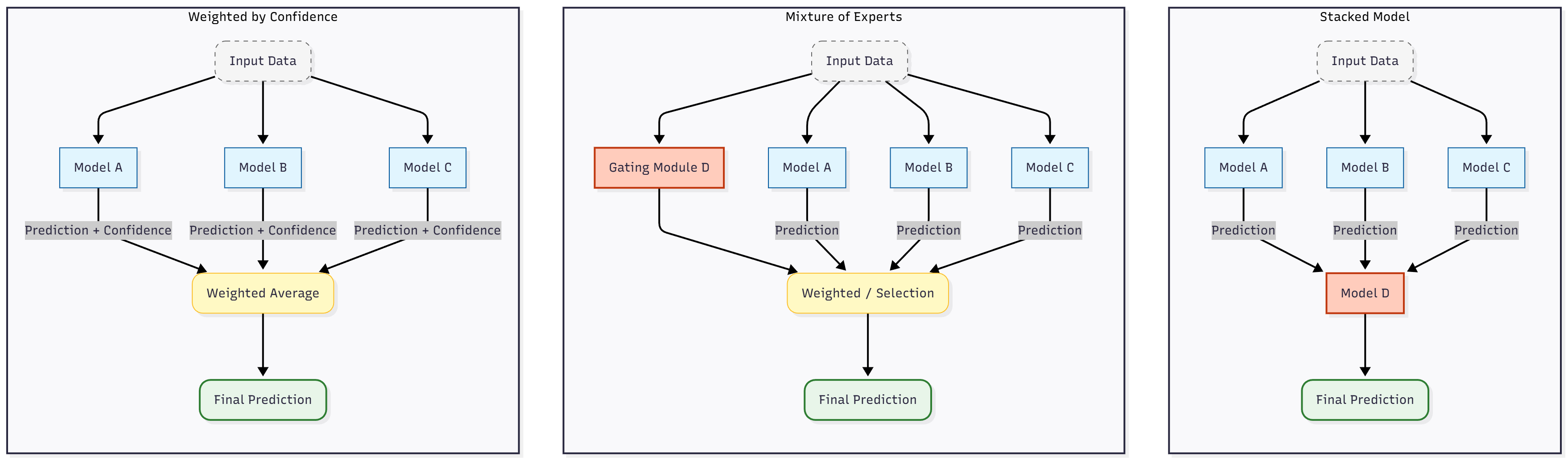

The simplest and most naive ensemble methods are, just like the ox guessing and the quiz show, taking the median or mean for numerical predictions (like price, temperature), and majority voting for categorical predictions (like win/loss, action selection). Of course, there are various advanced methods:

- Weighted Average/Voting: Assigning weights based on the model’s confidence level or its historical accuracy.

- Mixture of Experts (MoE): Training a new module that, before each prediction, selects a few most suitable models to make the call, then integrates them.

- Stacking: Training a new model to make the same prediction, but using the predictions of all the weak models as its input features.

While designed for predictive models, these intuitive ensemble methods also apply to human groups.

Take weighted averaging as an example. One problem with taking a direct median or majority vote is that everyone’s guess or vote counts the same. However, individual confidence in their own decisions fluctuates in different situations. If everyone in the group honestly provided their confidence level along with their prediction, the quality of the ensemble based on this weighted average/vote would be significantly higher. The problem here is that giving an “accurate confidence level” is itself a difficult task.

Douglas W. Hubbard describes in his book How to Measure Anything how his IT consultancy “quantifies everything.” Since he often cannot obtain massive amounts of raw data from client companies for statistical analysis, his team has to extract numerical uncertainty from conversations with client interviewees. The issue is that humans are an overly confident species: almost everyone is overly optimistic about the confidence of their answers. So, he designed a series of questions to let interviewees first “calibrate” their subjective estimation confidence intervals. Below is a set of questions from the book. If you are interested, you might want to test your own confidence “calibration.” The “90% Confidence Interval” in the table means that you are 90% sure that the correct answer lies between the “Lower Bound” and “Upper Bound” numbers you fill in. Unfamiliar with the topic? Don’t know the answer? Perfect! Because these questions are meaningless to people who know the exact answer; what it wants is the uncertainty of your guess. The answers and the method for calculating calibration can be found in the appendix at the end of the article3.

| No. | Question | 90% Confidence Interval (Lower Limit) | 90% Confidence Interval (Upper Limit) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | What is the air distance between New York and Los Angeles in miles (1 mile = 1609.344 meters)? | ||

| 2 | In which year did Sir Isaac Newton publish the Law of Universal Gravitation? | ||

| 3 | How many inches long is a typical business card? | ||

| 4 | In which year was the Internet established as a military communication system? | ||

| 5 | In which year was Shakespeare born? | ||

| 6 | What was the new speed record set by a British steam locomotive in 1938 (in mph)? | ||

| 7 | What percentage of a square’s area is covered by a circle of the same diameter? | ||

| 8 | How old was Charlie Chaplin when he died? | ||

| 9 | How many pounds did the first edition of this book weigh (1 lb = 453.5924 g)? | ||

| 10 | On what date did the US sitcom “Gilligan’s Island” first air? |

| No. | Question (True or False) | Response (T/F) | Confidence Level (Circle one) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ancient Rome was conquered by Ancient Greece. | 50% 60% 70% 80% 90% 100% | |

| 2 | Three-humped camels do not exist. | 50% 60% 70% 80% 90% 100% | |

| 3 | 1 gallon (1 gal = 3.785 L) of oil is lighter than 1 gallon of water. | 50% 60% 70% 80% 90% 100% | |

| 4 | Viewed from Earth, Mars is always farther away than Venus. | 50% 60% 70% 80% 90% 100% | |

| 5 | The Boston Red Sox won the championship of the first World Series. | 50% 60% 70% 80% 90% 100% | |

| 6 | Napoleon was born on the island of Corsica. | 50% 60% 70% 80% 90% 100% | |

| 7 | “M” is one of the 3 most commonly used letters. | 50% 60% 70% 80% 90% 100% | |

| 8 | In 2002, the average price of a desktop computer was less than $1,500. | 50% 60% 70% 80% 90% 100% | |

| 9 | Lyndon B. Johnson was a governor before becoming Vice President. | 50% 60% 70% 80% 90% 100% | |

| 10 | 1 kilogram is heavier than 1 pound. | 50% 60% 70% 80% 90% 100% |

Reporting confidence ultimately relies on individual honesty and confidence calibration. If we can estimate individual “accuracy” based on historical behavior, ensemble methods can adopt relatively more objective weights.

Ray Dalio explains in his book Principles how his hedge fund, Bridgewater, uses a dot collector system to conduct team decision-making during meetings: the company has employees rate each other openly on a scale of 1-10 on various traits, comprehensively measuring the so-called “believability” of each employee in different fields based on historical opinions. Then, when voting on company or team decisions, everyone’s vote is weighted according to the traits required for that decision. The believability here is no longer a self-assessment but relies on the ratings of those around you regarding your past performance on similar traits. That is to say, the weight of a person’s speech or vote on a current topic is determined by how the team views that person’s past performance on similar topics. This can be thought of as a “weighted vote based on historical accuracy” and can also be considered a “Mixture of Experts” executed according to certain fixed rules. If you want to avoid “amateurs leading experts” while accepting open multi-dimensional ratings among team members, Dalio’s mechanism might be worth borrowing.

There are many more interesting algorithms and examples of extracting high-quality information from crowd wisdom that cannot be listed one by one. Such as Crowdsourcing Aggregation: when the same dataset is labeled by multiple personnel, how to deduce labels that are more accurate (than simple majority voting) from low-quality results that may contain numerous human errors (cheating for labor fees via random labeling, malicious sabotage, or misunderstanding of labeling tasks, etc.). Or Prediction Markets: collecting mass estimates of probabilities (odds) for future events like political elections and sports/entertainment results from ordinary people through financial incentives similar to stock trading and betting.

Not all applications have a way to measure the “accuracy” of the ensemble results. How to use crowd wisdom has also been the foundation of various Mechanism Design and Social Choice Theory in politics and economics: voting systems, jury systems, public goods auction mechanisms, etc. These fields may not have metrics to directly compare the quality of ensemble results, so they judge the superiority of algorithms/mechanisms by proving whether they logically satisfy some reasonable basic assumptions. For example, if all voters think A is better than B, then A should rank higher than B in the final tally result4. In other words, the political and economic fields generally use a series of abstract “thought experiments” to verify algorithms/mechanisms, rather than relying on hard-to-obtain data verification. But other than that, algorithms/mechanisms for aggregating information are not fundamentally different: they are all methods for integrating the opinions of a large number of individuals into a collective form5.

In fact, Galton’s conclusion at the end of that article about guessing the ox’s weight was:

This result is, I think, more creditable to the trustworthiness of a democratic judgment than might have been expected.

This is why the article was titled “Vox Populi” (Voice of the People). From the perspective of ensemble algorithms and mechanism design, there is no mathematical difference between AI models and humans. As long as individuals are independent and diverse, the wisdom of the crowd is essentially a free lunch.

Making Models Humans

Reading this, you might be unimpressed: What does this have to do with me? I don’t guess numbers or compete in quizzes every day, nor do I want to be objectified into an information source or rated by colleagues around me; I don’t have the time to ask a bunch of people about everything, and there isn’t a crowd around me ready to be asked at any moment; for most ordinary people who are neither CEOs nor those in power, “dragon-slaying arts” like corporate management and social mechanism design seem useless.

In fact, the times have changed.

Right now, stationed in your computer and phone is a knowledgeable, on-call, fast-responding brain trust: Large Language Models (LLMs). They are not just “average joes,” but “sages” whose intellectual level may far exceed human individuals. Since human group opinions and AI model predictions can be integrated using the same methods, conversely, LLMs can be organized and managed like human groups.

Some people use LLMs very intuitively: ask a question, see if the answer is useful; if not, either leave or continue to ask follow-up questions. Others hate the inconsistency of LLM answers to the same question, so they turn the temperature parameter to 0 to get deterministic results. The former treats the LLM as an individual, while the latter treats the LLM as a program. Individuals are not scalable/parallelizable, while programs lack endogenous complex diversity. In this way, the power of LLMs is not fully unleashed.

For example, you can talk to at least two different LLMs side-by-side and get multiple answers to compare simultaneously. Randomness is great; it brings multiple perspectives. Since LLMs trained behind closed doors by different companies have significant differences in thinking styles, this satisfies the key condition of crowd wisdom to a certain extent: diversity. Being able to communicate in parallel increases time efficiency dramatically.

Many people go further. For instance, Andrej Karpathy recently formed an LLM Council. For every question he asks, 4-5 LLMs from different companies first answer independently, then “peer review” each other’s answers, and finally, a “Chairman” submits the final result based on this series of discussions. Sounds complicated? Leaving aside that he built this council program in just one Saturday (with 90% of the code generated by LLMs), this ensemble strategy resembling “Stacking” should perhaps become the default way to handle complex problems. LLM time is cheap (the council mode only adds the serial time consumption of review and summary steps), while your precious human time shouldn’t be spent manually correcting results that haven’t been fully negotiated by LLMs and integrated via crowd wisdom.

Now, do you understand the mindset of your boss or employer a little better? Yes, you might not be a CEO; but in this era, you are still managing countless smart people. Crowd wisdom, model ensemble techniques, social choice mechanism design… these might have made it into the “Introduction to LLM Management” from which every human can benefit.

But to truly treat LLMs as “humans” possessing crowd wisdom, there is a problem. A crucial premise of crowd wisdom is that “the crowd possesses a certain diversity.” In a group lacking diversity—that is, when most individuals are influenced by the same type of thinking—ensemble methods not only fail to bring benefits in accuracy but also amplify the bias of the results. Experiments have shown6 that simply letting everyone know the average opinion of others before answering individually is enough to drastically reduce the diversity of the entire group’s answers and increase ensemble prediction bias. Not to mention the phenomena of herd mentality due to over-reliance on opinion leaders and group polarization caused by only willing to express opinions within “echo chambers” under today’s pervasive social influence.

If human group diversity is easily eroded by acquired social influence, then the diversity defect of LLMs is innate—they were stuffed into the same mold from birth. LLMs are first “pre-trained” on massive text produced by humans. This in itself limits the diversity of the models—after all, there is very little human text left that hasn’t been included in the training set. Even if all the text produced by human civilization is diverse enough, before LLMs can be released by major companies and research institutions to communicate with you after pre-training, they need to undergo “Alignment.” Alignment refers to making LLM speech safe and harmless, conforming to human values. LLMs that have been aligned into the “ideal human echo chamber” will refuse to answer “how to make biological weapons” and will not mock or scold you when you are sad. This is a process that must be carried out for safety in various senses, but it also further reduces indicators like the LLM’s lexical diversity7, conceptual diversity8, and linguistic creativity9.

Lacking diversity, LLMs struggle to present crowd wisdom. Apart from the usage habits mentioned above—“using LLMs from different companies/sources simultaneously” and “not setting the temperature parameter to zero and asking randomly multiple times”—what else can ordinary users do?

At the end of this article, I will share two interesting and simple prompt engineering tricks I recently learnt. Since it is difficult to sample diverse answers directly from the LLM model, we use verbal language in the prompt to command it to sample randomly:

- Verbalized Sampling10: Ask the LLM to “randomly sample from the tail of the distribution,” listing multiple uncommon, non-stereotypical results at once.

- String Seed of Thought11: Let the model first simulate a “random seed” (gibberish string), then “forcefully think” of a unique angle to answer the original question based on this seed.

Let’s illustrate with a practical example. I asked the model to write a couplet (two lines of poetry) for the cover of the classic novel Dream of the Red Chamber, assuming it was published for the first time today.

Assume Dream of the Red Chamber is published for the first time today. Please generate an original two-line, seven-character poem for the book cover copy.

I asked Gemini 3 (Thinking mode, Temperature 1.0) five times with the prompt above. The answers were (translated):

Half a life of splendor returns to a dream, the sky full of wind and snow covers the Red Chamber.

Having seen through all splendor, it is ultimately an illusion; just watch the white snow fall on the Red Chamber.

Splendor burns out returning to white snow, foolish tears dry up entering absurdity.

Splendor fully read ultimately becomes an illusion, ten thousand beauties mourn together, tears making the book.

Half a life of splendor returns to a dream, the sky full of wind and snow buries the Red Chamber.

Every first line contains “Splendor”. Three out of five second lines contain “Red Chamber”, and four out of five lines feature “Snow.” It is quite monotonous.

Now, adding the Verbalized Sampling prompt:

Please randomly sample five different answers from the tail of the probability distribution, such that the probability value of each answer does not exceed 0.10.

Assume Dream of the Red Chamber is published for the first time today. Please generate an original two-line, seven-character poem for the book cover copy.

The same Gemini 3 answers (reformatted):

Splendor may not defeat loneliness; to this day, I regret being the Stone that mended the sky.

Borrowing the pen of gratitude and vengeance from heaven, writing a gut-wrenching book in the human world.

Pink skeletons are all white bones, vast snow covers the romantic flow.

Startling the Song of Rainbow Skirt and Feathered Robe, crying awake the person in the Yellow Millet Dream.

Mistakenly entering the Gold and Jade trap of the red dust, only to know that Wood and Stone were the original heart.

Because it was a single response generation, it deliberately avoided semantic repetition. It claimed, “By lowering the weight of common phrases, I selected original verses with more novelty, unique perspectives, or more unfamiliar wording, trying to avoid clichés.”

The String Seed prompt template is longer:

You must generate a diverse response. To do this, first generate a unique and complex random string as a seed. This random string should look sufficiently complex and unpredictable, with no obvious structure or pattern. Use your judgment to ensure it looks arbitrary and guess-proof. If the user asks a question that allows for multiple answers, think deeply and carefully about the user’s question and use the generated seed to generate an answer, ensuring that your single answer is unique and diverse. Please use the full content of the string to extract maximum randomness.

Assume Dream of the Red Chamber is published for the first time today. Please generate an original two-line, seven-character poem for the book cover copy.

Asked five times to Gemini 3 (think), the results (formatted as “Result - Random Seed”):

Splendor burns out returning to white snow, eternal love obsession is hard to settle. 9X#kL2mP!v8zQ^w7jRb5@nCd3%Y

Ten thousand feet of red dust is brittle as glass, a great dream leaves no trace in the snow. G9z#7Q@x2mL!5kP8bW^4nR(0)yJ%1vD

Half a roll of absurdity writes the flavor of the world, a life of foolishness is paid to the red dust. r7B#9zL!q2W@mX5$kPyN4jD8^vH3%tF1

Bell-ringing and tripod-eating families ultimately turn to illusion, tears sprinkled on empty steps bury the fallen red [flowers]. 8zX@q9#L2mR5kP!1wBOcJ^7vN4

Sky-high wealth ultimately becomes an illusion, the debt of the eternal love demon is real. w#9LkR@2mPz!8xQv%5NbJ^4yF(7hT0)cG3D1µ

Although there is still some overlap in wording and imagery, it is much better than the initial attempt.

In the scenarios I’ve tried, Verbalized Sampling generally works better and is extremely convenient to use. It can be placed before any question or directly used as a default system prompt prefix. It is recommended for creative writing.

Of course, besides these two less intuitive tricks, there is an obvious, purer pursuit of diversity, a follow-up method that is even effective on humans: “Give me an answer different from the previous one.” In my personal experience, asking this frequently to yourself yields surprisingly good results.

Conclusion

In this era, the challenge of crowd wisdom facing humanity is slightly inverted: in the past, we struggled to make “humans” collaborate rationally and follow rules like models, playing as pawns on a grand chessboard; now, we rack our brains to make “models” adapt to unknown environments like humans, becoming active substitutes for diverse social roles. In this process, many things will be upended.

But in any case, from the livestock market guessing game to the AI council at your fingertips, from integrating human opinions to organizing AI teams, the basic principles of crowd wisdom will not change due to the object: Diverse perspectives and effective integration mechanisms will always be the key prerequisites and the mainstay.

According to official data, the Eiffel Tower is currently 330 meters (1,083 feet) tall due to new antennas. Before 2022, it was 324 meters (1,024 feet). ↩︎

To be slightly more rigorous, the first condition can be restated as: there must be some individuals in the group whose probability of answering correctly is better than random selection or pure noise; the second condition: given a problem, an individual’s answer must not depend entirely on the answers of others (e.g., herd behavior, playing devil’s advocate, or intentional/unintentional collusion). ↩︎

The correct answers to the questions are in the image below. The calibration of the numerical estimates in the first half is the proportion of correct answers that fall within your upper and lower bounds: if it is exactly 90%, then your calibration is perfect; most people will be far below 90%, which means we are generally too optimistic about our estimates. The calibration calculation for the True/False judgment in the second half is relatively more complex: first note the proportion you got right, then calculate the average of all the confidence levels you circled. If the former is less than the latter, it indicates your estimates are too optimistic. How to Measure Anything states that practicing such questions can significantly improve your subjective confidence calibration over time.

↩︎No. Question Answer 1 What is the air distance between New York and Los Angeles in miles (1 mile = 1609.344 meters)? 2451 2 In which year did Sir Isaac Newton publish the Law of Universal Gravitation? 1685 3 How many inches long is a typical business card? 3.5 4 In which year was the Internet established as a military communication system? 1969 5 In which year was Shakespeare born? 1564 6 What was the new speed record set by a British steam locomotive in 1938 (in mph)? 126 7 What percentage of a square’s area is covered by a circle of the same diameter? 78.5% 8 How old was Charlie Chaplin when he died? 88 9 How many pounds did the first edition of this book weigh (1 lb = 453.5924 g)? 1.23 10 On what date did the US sitcom “Gilligan’s Island” first air? 1964.9.26 No. Questions Answer 1 Ancient Rome was conquered by Ancient Greece. False 2 Three-humped camels do not exist. True 3 1 gallon (1 gal = 3.785 L) of oil is lighter than 1 gallon of water. True 4 Viewed from Earth, Mars is always farther away than Venus. False 5 The Boston Red Sox won the championship of the first World Series. True 6 Napoleon was born on the island of Corsica. True 7 “M” is one of the 3 most commonly used letters. False 8 In 2002, the average price of a desktop computer was less than $1,500. True 9 Lyndon B. Johnson was a governor before becoming Vice President. False 10 1 kilogram is heavier than 1 pound. True This seemingly obvious “consistency” assumption is not always met. For instance, some mechanisms involving multiple rounds of voting might result in a scenario where A is eliminated by C first, and then B is elected as the majority’s second choice. ↩︎

If you read my previous post “Explaining Elo Rating from Scratch,” you might have already made the connection: Elo rating is, in fact, an ensemble method that synthesizes individual results expressed in “comparison” form (match wins/losses) into a macro collective result expressed in “sequence” form (player ability). You just need to replace “match wins/losses” with “personal preference information for any two candidates” and “player ability” with “overall candidate popularity” to reproduce a special social voting mechanism. ↩︎

Lorenz et al., How social influence can undermine the wisdom of crowd effect. https://www.pnas.org/doi/epdf/10.1073/pnas.1008636108 ↩︎

Kirk et al., Understanding The Effects Of RLHF On LLM Generalisation And Diversity. https://arxiv.org/pdf/2310.06452 ↩︎

Murthy et al., One fish, two fish, but not the whole sea: Alignment reduces language models’ conceptual diversity. https://arxiv.org/pdf/2411.04427 ↩︎

Lu et al., AI as Humanity’s Salieri: Quantifying Linguistic Creativity of Language Models via Systematic Attribution of Machine Text against Web Text. https://arxiv.org/pdf/2410.04265 ↩︎

Zhang et al., Verbalized Sampling: How to Mitigate Mode Collapse and Unlock LLM Diversity. https://arxiv.org/pdf/2510.01171 ↩︎

Misaki and Akiba. String Seed of Thought: Prompting LLMs for Distribution-Faithful and Diverse Generation. https://arxiv.org/pdf/2510.21150 ↩︎